The Air Force’s 50,000 Ton Press

In Cleveland, Ohio, resides one of the largest and most powerful presses in the world, the Alcoa 50,000 ton press. This is enough for to lift an Iowa-class battleship – but what did the Air Force possibly need such a machine for?

The 50,000 ton press has earned a place as one of the single most important manufacturing machines in the United States, functioning as one of the only places in the country that can press forge complex components for use in aircraft.

Measuring 12 stories tall and weighing 8,000 tons, the press was built in the 1950s, and remains in use today.

Contents

Background

The existence of the “Fifty”, as it is known to those who work with it, dates all the way back to the end of the First World War.

The Treaty of Versailles impacted numerous areas of Germany’s industry, including their iron-production capabilities. Much of this had to be given up, but they were still able to produce plenty of magnesium.

Magnesium has many uses in engineering; it is the lightest metallic element, is strong, weldable, and can be manipulated into different shapes. It has one drawback though: it is brittle.

Other commonly used metals, like iron, are quite flexible.

Iron and steel can be easily hammered into shape, like with a forging hammer. Image by Deutsche Fotothek CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

Iron and steel can be easily hammered into shape, like with a forging hammer. Image by Deutsche Fotothek CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

In short, you can bend iron into shape. Try bending magnesium though, and it cracks. Germany got around this flaw by pressing magnesium into shape, rather than beating it. This is known as press forging, and it can be used to quickly and easily create extremely complex shapes.

This process also works with aluminium, and naturally, press-forged components from these materials were used extensively in German aircraft, as they were both light and strong.

These components were found by the Allies, and the US was impressed.

Deducing that they were being created with a large press, the US began a project to build their own press to speed up aircraft production. However, the war ended before this could finished.

A 15,000 ton press in the Friedrich Krupp AG factory in, Essen, Germany.

A 15,000 ton press in the Friedrich Krupp AG factory in, Essen, Germany.

When Allied experts inspected German industrial plants after the war, they found that they had indeed built giant presses. They had two 15,000 ton presses, and a massive 30,000 ton press.

The US took the 15,000 ton presses, but unfortunately for them, the Soviets took the 30,000 ton unit. Aware that the Soviets were now able to create complex, lightweight and strong structures for their aircraft, the US began a large-scale project to solve this pressing issue.

With the backing of the US Air Force, the US started the Heavy Press Program in 1950. This program… well it produced heavy presses, but it also built up the knowledge base and training surrounding this new production technique.

The 30,000 ton Schloemann closed die press at the Bitterfeld factory. This press was taken by the Soviets, and is still in use today at the Kamensk-Uralsky Metallurgical Works in Russia.

The 30,000 ton Schloemann closed die press at the Bitterfeld factory. This press was taken by the Soviets, and is still in use today at the Kamensk-Uralsky Metallurgical Works in Russia.

Some defense contractors viewed the participation in this new industry a risk, but they certainly couldn’t have predicted how important these presses would become in the United States’ dominance in the air.

It ran until 1957, by which point the US had squeezed out 10 enormous forging machines. These were 6 extruders, and 4 hydraulic presses. Many of these machines remain in use today.

A few 35,000 ton presses were built, but the biggest and most famous was the monstrous 50,000 ton press, known simply as the “Fifty”.

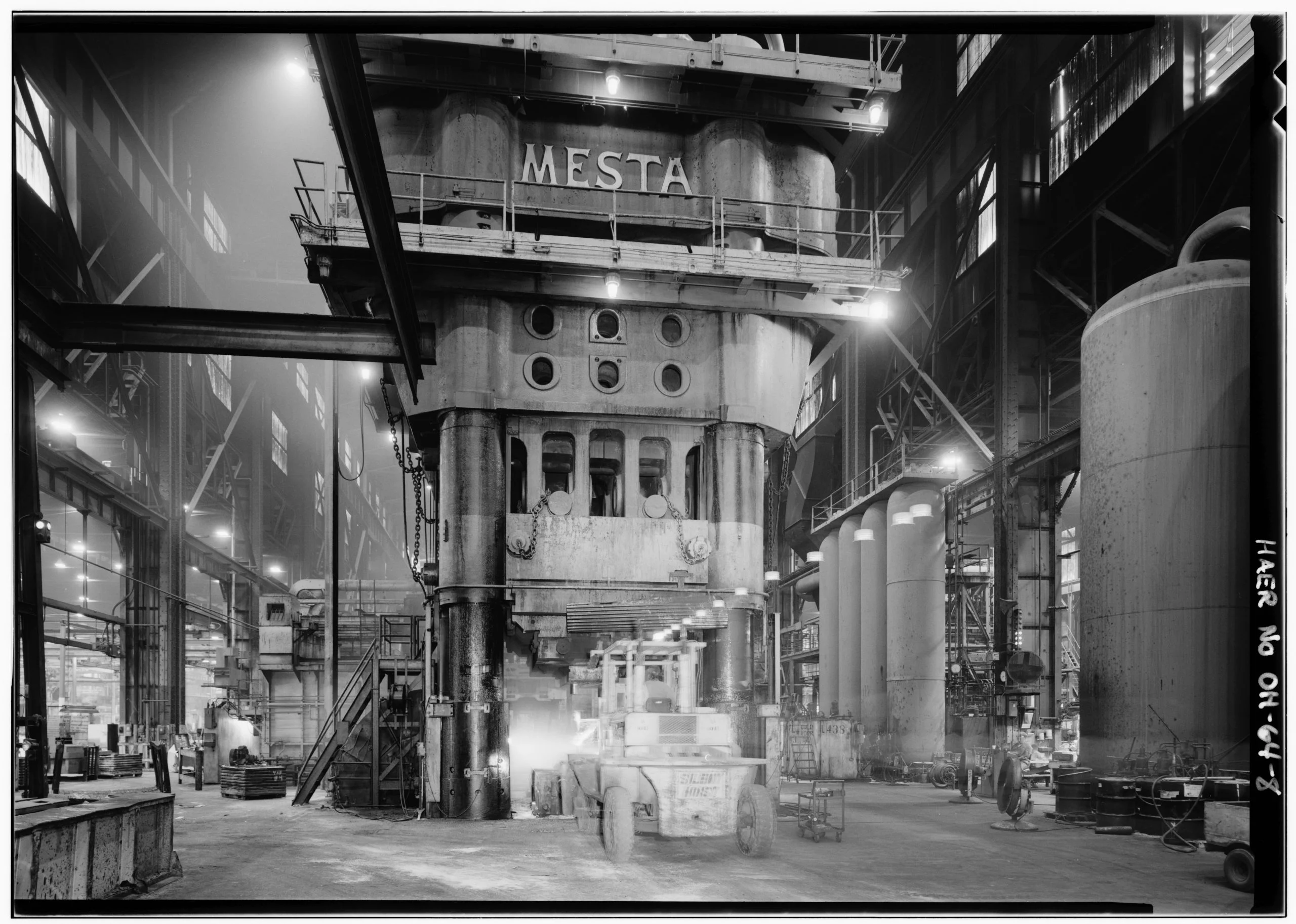

The 50,000-ton press inside Air Force Plant 47 in Cleveland, Ohio.

The 50,000-ton press inside Air Force Plant 47 in Cleveland, Ohio.

In 1952, Air Force Plant 47 began construction in Cleveland, Ohio, specifically to house these new presses. Operations at the plant began in 1955, with the operating contractor being the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa).

The Mesta 50,000 Ton Press

The job of creating a press that is theoretically capable of lifting a battleship was given to industrial machinery manufacturer Mesta Machinery, based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Designing and building such a machine was an incredible feat of engineering.

The full press has a total height of 285 ft (87 meters), with 118 ft (36 meters) of that passing through the floor into a basement below. The Fifty’s total weight is around 8,000 tons.

A cutaway showing the full height of the Mesta 50,000-ton press. Note the columns running from top-to-bottom.

A cutaway showing the full height of the Mesta 50,000-ton press. Note the columns running from top-to-bottom.

It is constructed from 16 enormous steel castings, some of which weighed over 350 tons each – making them some of the largest single castings ever made.

These castings were poured by Mesta at their own facilities, and were then machined to within tolerance by a custom-made 18 inch milling machine.

To make up the Fifty, these castings were stacked on top of each other in sections. The lowest two levels sat below the floor in the basement, and weighed 800 tons.

One of the enormous castings used in the press. This is the top-most section on its side. It contains the pressure cylinders at the top of the press. Note the person on the right for scale.

One of the enormous castings used in the press. This is the top-most section on its side. It contains the pressure cylinders at the top of the press. Note the person on the right for scale.

On top of these lower levels is the lower die, which is the shaped surface that the material will be pressed into.

Above this is the crosshead, which is the portion that actually moves up and down and contains the upper die. All in, this moving assembly weighs 1,150 tons. At the very top of the press are eight hydraulic pressure cylinders that generate the crushing force needed to press the material into shape.

The whole press is held together by eight 76-ft tall steel-alloy columns that run from the very bottom to the very top of the machine. This columns are engineering marvels of their own.

One of the huge steel columns being forged from a 270 ton steel ingot.

One of the huge steel columns being forged from a 270 ton steel ingot.

They began as enormous castings before being forged into shape. They were then heat treated in a huge 112 ft-long furnace. Mesta’s initial forgings were so accurate that machinists only had to remove one inch from the columns to achieve the perfect finish – this was done by a 96 inch lathe.

The columns measured 40 inches in diameter, and were threaded in four sections. Massive 55-ton nuts measuring 52 inches in diameter were fitted onto these threaded sections.

The hydraulic medium is water, mixed with a small amount of oil for lubrication and rust-prevention. Pressure is generated by pumps powered by 1,500 hp motors.

The basement below the press. This room contains the press’s foundations.

The basement below the press. This room contains the press’s foundations.

Fluid pressurised to 4,500 psi is sent to huge accumulator bottles, which then transfer this into the eight cylinders at the top of the press when needed.

As the 60 inch-wide cylinders are pressurised, the press moves down with a force of up to 50,000 tons – enough to lift an Iowa-class battleship if the press was flipped upside down.

The hydraulic fluid’s flow direction is reversed to lift the crosshead back up.

A close view of the die inside the press. Ingots of metals like titanium and aluminium will be placed in here, and literally squished into shape.

A close view of the die inside the press. Ingots of metals like titanium and aluminium will be placed in here, and literally squished into shape.

But one of the most impressive things about this press is how precisely it can deliver this earth-shattering force.

A complex systems of valves allows a single operator to control the press instantly and incredibly accurately with the simple movement of a three-inch long lever.

The working stroke of the Fifty is one-foot, with a maximum stroke of six-feet. It optimises the production of complex aircraft components as it can stamp them at a relatively fast pace of 30 per minute.

This is much faster than machining parts individually.

Damage and Repair

After coming online in 1955, the Fifty has continued in use ever since, playing a crucial role in the manufacture of virtually all of the US’s major military aircraft. This has ranged from the F-15, to the advanced F-35 and even spacecraft.

It has been critical for manufacturers like Boeing and Airbus, who use it to make key components in their aircraft.

However in 2008, after 53 years of service, cracks were found in the Fifty’s lower sections. Similar issues had been found in the 1970s, but this time the machine needed a major overhaul in a financially unstable economy.

Space Shuttle components created by the press.

Space Shuttle components created by the press.

Alcoa, who still operate the press, were forced to consider a few options. They could scrap it, try to repair the cracks, or remake major components.

Scrapping was never really a real option considering the machine’s importance, and repairing the damage wouldn’t guarantee long future usage. Therefore Alcoa started a huge $100 million project to overhaul the Fifty.

Alcoa hired Siempelkamp, a German press-builder, to cast new sections for the press. They were to reuse the main columns and cylinders, and only replace the necessary components.

Titanium F-15 bulkheads before (left) and after (right) being press by Alcoa’s 50,000 ton press.

Titanium F-15 bulkheads before (left) and after (right) being press by Alcoa’s 50,000 ton press.

But this overhaul allowed the wonders of modern engineering to actually upgrade the press. One such upgrade was switching the sections’ construction material from steel to ductile iron. Iron is much more flexible than steel, and this will increase the life of the sections.

A redesigned control system gives Alcoa even more precise control of the press, at a varying range of pressures and die sizes.

This has increased the complexity of the shapes they forge, opening the opportunity for the manufacturer of components that were previously impossible to make.

Pressing material is often heated to high temperatures to increase its malleability.

Pressing material is often heated to high temperatures to increase its malleability.

Alcoa’s 50,000 ton press has served the US for 70 years now, helping to produce some of the most technologically advanced machines humanity has ever created.

Starting from an Air Force project in the 1950s, its safe to say the Fifty’s service has been a crushing success.