At the 50th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg, Union (left) and Confederate (right) veterans shake hands at a reunion, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. 1913.

The 1.5 million Union and perhaps 600,000 Confederate veterans were very visible members of post-war society. For one thing, they dominated political offices in both the North and the South. Most U. S. presidents during this period had fought for the Union, and scores of veterans from both sides served as governors, senators, and congressmen, while countless thousands served in state and local offices. But veterans’ importance to American society and to the legacies of the Civil War transcended their political influence.

By the 1880s, many Americans would have walked past monuments to Civil War soldiers in town squares, cemeteries, or other public places in the North and South. But the “old soldiers,” as they were already being called, were still only in their forties or fifties and still very much a part of the communities in which they lived.

They were most prominent as members of veterans’ organizations and as participants in Memorial Day commemorations and July Fourth celebrations.

Civil War veterans formed many different veterans’ associations. Some consisted of all the men living in a single town or county, while others were formed by survivors of specific armies, corps, regiments, or even companies, and still, others were formed by unique groups like prisoners of war or members of the signal corps. But two organizations dominated.

By the 1880s, as many as 400,000 former Yankees belonged to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which was founded in 1866 and reached its membership peak twenty years later.

A veteran of the Union Army shakes hands with a Confederate veteran at the Gettysburg celebration, in Pennsylvania. 1913.

The United Confederate Veterans (UCV) grew out of a number of smaller associations in 1889 and boasted 160,000 members by 1900. The GAR and UCV organized at the national, state, and local levels, with the local “posts” named after famous generals or local heroes.

A number of “soldiers’ newspapers” were published to support the activities of the GAR and UCV. Papers like the American Tribune, National Tribune, and Ohio Soldier published war memoirs, reports from soldiers’ reunions, and information about pensions for GAR members, while the Confederate Veteran was the official publication of the UCV for forty years.

Memorial Day parades and speeches made it easy for Americans to think of Civil War veterans as distinguished old men with gray beards, elegant bearings, and bittersweet memories of lost comrades.

In fact, the lives of Union and Confederate veterans were much more complicated. They were often able to blend back into families and communities fairly easily, but, like veterans of any war, some found it more difficult to readjust to civilian life.

Although many Civil War veterans were very successful after the war in business, politics, and life, many believed that the war had prevented them from meeting their expectations for economic success.

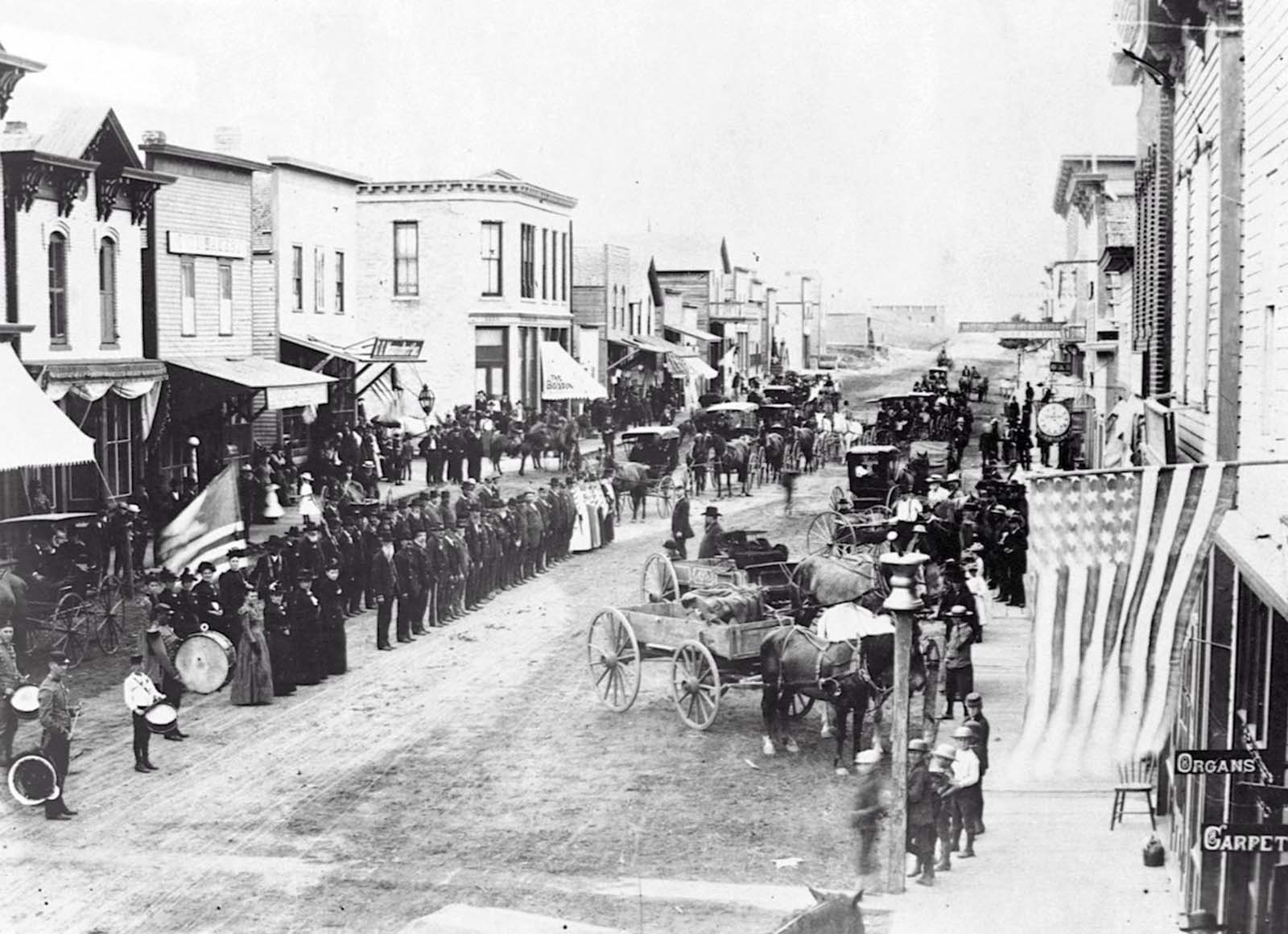

Civil War veterans on Fourth of July, or Decoration Day, on review on the main street of Ortonville, Minnesota. 1880.

They had spent the best years of their young manhood in the army. Union soldiers had been away while the men who remained at home profited from the booming economy, while Confederate soldiers saw family fortunes and farms crumble under the pressure of invasion and the collapse of the slave economy.

Although the term “post-traumatic stress” is a modern way of describing the effects of war on some individuals, the condition was certainly known during and after the Civil War.

The failure of a man’s courage in the face of combat or when confronted with having to support a hard-pressed family after the war was usually attributed to a failure of will or masculinity rather than to a medical condition.

But “soldier’s heart,” as some people called it, clearly affected countless soldiers on both sides, who ended up in state asylums for the insane suffering from delusions, insomnia, paranoia, and other symptoms that were just beginning to be understood in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

About 617,000 Americans were killed during the Civil War. The number is equal to the entire number of Americans who had died in all wars up to that point, including both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

Marion, Indiana — Veterans eat their meals in the dining hall of the National Soldiers’ Home, a facility for the care of disabled American veterans, many from the Civil War. 1898.

Manassas, Virginia — Veterans of the Civil War meet on the Bull Run Battlefield for a reunion celebration. 1913.

Parade of the Grand Army of the Republic during the 1914 meeting in Detroit, Michigan. 1914.

Civil War veterans attend the funeral of General Horace C. Porter. 1921.

Chattanooga, Tennessee — A group of Confederate cavalry veterans gather at a reunion. 1921.

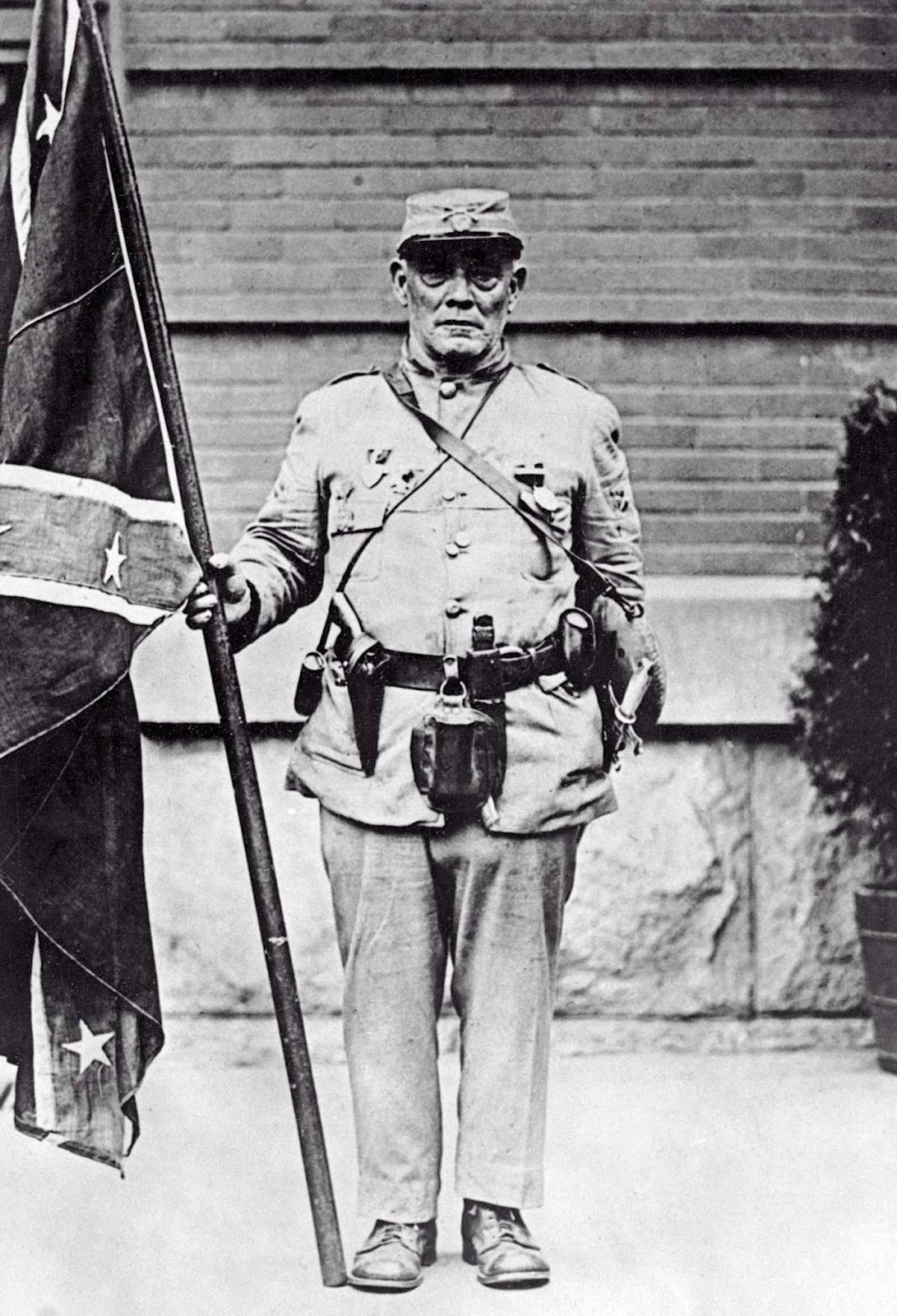

Richmond, Virginia — J. F. Griffin, at 81 the last surviving member of the Louisiana Tigers, holds a Second Naval Jack flag at the 32nd Annual Reunion of the United Confederate Veterans at Richmond. 1922.

Washington, D.C. — President Harding receives veterans of the Confederate Army who have been attending their annual reunion at Richmond, Virginia. Old soldiers who fought under the Stars and Bars during the Civil War are shown here with the president, who welcomed them to the White House. 1922.

Elderly Civil War veterans playing cards together. 1930.

Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania — Veterans of the Civil War pose at High Water Mark Memorial. 1931.

Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania — Union Civil War veterans stand in front a monument at Gettysburg. 1931.

Rochester, New York — The Grand Army of the Republic Civil War Veterans join a parade down main street during Rochester’s centennial. 1934.

Washington, D.C. – Captain R.D. Parker, age 90, who played a drum at Lincoln’s inauguration, as he took part in the final parade of the Grand Army of the Republic in Washington, D.C., closing the 70th annual encampment. The Grand Army of the Republic was an organization founded in 1866 for veterans of the Civil War. 1936.

At the Memorial Day parade, Civil War veteran, George W. Collier, 97, shows Alwin Sharr, 9, a boy scout cub, how he aimed his rifle during the war. 1939.

John S. Dumser, 101-year-old veteran of the Civil War. 1949.

Elderly Civil War veteran Thomas Evans Riddle. 1953.

Self-proclaimed “Confederate Civil War veteran” William Lundy sitting on his porch. 1956.

Self-proclaimed “Confederate Civil War veteran” sitting on his porch. 1956.

Self-proclaimed “Confederate Civil War veteran” walking through his yard. 1956.

Self-proclaimed “Civil War veteran” Walter W. Williams. 1953.

Serenaded Walter Williams lying in bed with a cigar. 1959.

Williams with friends. 1959.

Walter Williams lying in bed with cigar, surrounded by family and friends. 1959.

107 years old last remaining GAR Civil War Veteran Albert Woolson, relaxing on the couch while a little girl helps him sort through some mail. 1954.

107 years old last remaining Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Civil War Veteran Albert Woolson (seated) sitting in the front porch wearing a military hat and blanket while people and photographers are passing by. 1954.

Boys standing at attention for the funeral of a Civil War veteran who was the last member of the Grand Army of the Republic. 1956.

(Photo credit: The LIFE Picture Collection / Library of Congress / National Geographic Creative / Corbis. Text: James Marten / Union and Confederate Veterans).