Vengeance weapon one (V-1), the “buzz bomb,” the “doodlebug” or the “Fi 103” – whatever name you call it by, this impressive World War II-era German flying bomb was the world’s first operational cruise missile. Despite numerous proposals for a weapon of this type early in the conflict, the V-1 wasn’t put into use until 1944. Upon entering operation, the explosive was used in a consistent stream of attacks against London, in the hopes of breaking British morale.

V-1 ‘buzz bomb’ design

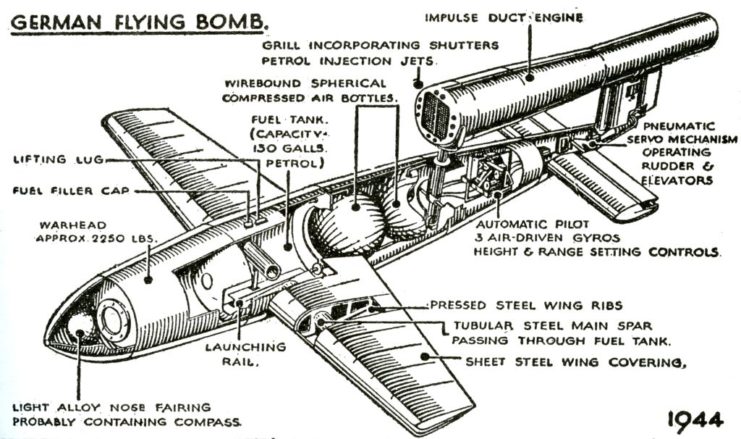

Diagram for the V-1 “buzz bomb.” (Photo Credit: SeM Studio / Fototeca / Universal Images Group / Getty Images)

The first flying bomb design was submitted to the Luftwaffe by Professor Georg Hans Madelung and aerospace engineer Paul Schmidt in 1935, yet nothing came of it. In 1939, Argus Motoren proposed a design for a remote-controled aircraft that could bomb targets, but this, too, was declined. It wasn’t until February 1942 that a collaboration between Fritz Gosslau and Robert Lusser yielded the basis for the V-1, after modifying parts of Schmidt’s earlier design.

The design was submitted to the Luftwaffe, who approved the project on June 19, 1942. It was produced under the name Flak Ziel Geraet – “anti-aircraft target apparatus” – to ensure enemy spies didn’t get word of it. The most unique feature of the design was the pulse-jet engine, which gave the bomb its distinct buzzing noise. This was caused by air entering the intake valve, mixing with fuel and then igniting, causing the shutters to open and close and thrust the aircraft forward.

Development of the V-1 ‘buzz bomb’

V-1 “buzz bomb,” 1944. (Photo Credit: ullstein bild / Getty Images)

The V-1 was equipped with a very simple guidance system consisting of a gyroscope, magnetic compass, barometric altimeter and a vane anemometer on the nose which, combined with a counter, determined when the bomb reached its target. Testing began in earnest in late 1942, first with a glide test and followed by a fully-powered flight. It wasn’t until May 26, 1943, after months of extensive testing, that the weapon was actually produced on a large scale.

Once fully operational, and with the design finalized, the explosive was capable of reaching a range of 250 KM, with a maximum speed of 400 MPH. It was also equipped with a 850-kg Amatol-39 warhead, which was eventually switched out for a Trialen one. Three fuses were used for detonation: one triggered on impact; one delayed, so the blast could go off deeper in the ground; and one triggered two hours after launch, to ensure the enemy couldn’t recover any duds.

Unique launch system

Allied soldiers inspect a launch ramp for a V-1 “buzz bomb” near Zutphen, the Netherlands, September 1944. (Photo Credit: Unknown Author / AFP / Getty Images)

Between 1944-45, over 30,000 V-1s were produced, with the Germans using forced labor. In fact, over 10,000 prisoners from Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp died while constructing the tunnels where they were built.

While the bombs were being made, launch sites were built throughout German-occupied territory. Most of them were located in the Pas-de-Calais area along the French coast, to ensure the V-1s were close enough to cross the English Channel.

The explosives were designed to be propelled from an inclined ramp after a push from a burst of high-pressure steam created by mixing hydrogen peroxide and sodium permanganate. It was directed into a tube that contained a piston, which was propelled forward to launch the bomb. V-1s could also be dropped from German carrier aircraft. However, this was reserved for much later in the war, once the Allies began destroying the launch sites.

Operational use throughout World War II

Canadian soldiers sitting atop a German V-1 “buzz bomb,” which failed to reach its target in Britain, 1944. (Photo Credit: Worth / Keystone / Getty Images)

On June 13, 1944, the Germans launched their first V-1 attack against London – many others soon followed. Despite their initial shock, the public quickly realized that the best way to protect themselves was to get underground as soon as the buzzing sounded. They also learned that, when the buzzing stopped, it meant the bomb was diving out of the air.

It also didn’t take long for the British military to get into action, sending fighter pilots to intercept V-1s, setting up barrage balloons and better equipping the coast and cities with anti-aircraft guns. This was generally effective, as, by mid-1944, the majority of buzz bombs were destroyed when they reached the English coast.

The Allies also created targeted missions to destroy launch sites, such as Operation Aphrodite, and British Intelligence fed misinformation to Berlin about important targets or previous attacks. This meant the Luftwaffe were constantly setting V-1s to incorrect locations, which fell short of their intended mark.

Effectiveness of the V-1 ‘buzz bomb’

Damage caused by a V-1 “buzz bomb” at Montford Place, London, July 1944. (Photo Credit: George Greenwell / Mirrorpix / Getty Images)

Of the 30,000 V-1s produced by Germany, approximately one-third of them were fired at Britain. Despite London being their primary target, only 2,419 reached their desired locations. When they did land, however, they were fairly destructive, killing 6,184 people in the city and injuring a further 17,981.

Of the remaining bombs, 9,000 were fired at European targets, 2,448 of which were sent to Antwerp.

While these numbers make the V-1 bombing campaign sound fairly effective, the reality is that it wasn’t. Statistically, they only hit their target 25 percent of the time. What did work in their favor, however, was that they were far more economical than launching full Luftwaffe bombing raids like those seen during the early years of the war.

Generally speaking, the V-1s, although theoretically impressive, had little-to-no effect on the war, despite being an effective psychological weapon.