With armor like chainmail and razor-sharp claws, giant ground sloths were titans of the Ice Age. Now, scientists are unearthing new findings about a new species that lived around 10,000 years ago — and was found at the bottom of an underwater cave.

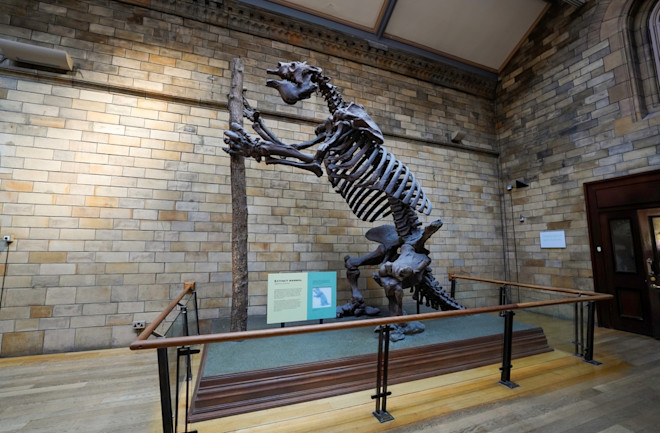

A giant ground sloth skeleton, an extinct mammal, towers over visitors to the Natural History Museum in London. (Credit: Old Town Tourist/Shutterstock)

Tree sloths have earned a reputation for being shy and slow-moving. But their ancestors, a diverse group of extinct creatures known as giant ground sloths, were not nearly as cuddly as their modern counterparts.

Sporting bony, chainmail-like armor and razor-sharp claws, these impressive beasts could be found lumbering throughout the prehistoric Americas during the last Ice Age — and not just on the surface, either.

Are Scientists Still Unearthing New Species of Giant Sloth?

In 2009, paleontologists discovered the fossils of a giant ground sloth in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. The scientists found the remarkably well-preserved sloth skeleton 100 feet below ground, in an underwater limestone cave. More recently, they’ve learned that the remains belong to an entirely new — albeit extinct — species of giant sloth.

The new species, later dubbed Xibalbaonyx oviceps, was the first in its genus to be uncovered, according to a 2017 paper published in Paläontologische Zeitschrift. Fittingly, ‘Xibalba’ is the name of the underworld in Maya mythology, given that the Maya used limestone caves as the sites for sacrificial rituals over a thousand years ago.

What Was an Ancient Sloth Doing in an Underwater Cave?

The fossilized sloth’s resting place was also unique. The creature died at the bottom of the El Zapote cenote, a massive, hourglass-shaped sinkhole that stretches down more than 170 feet. The sinkhole’s bottom spans more than 300 feet wide, and its ceiling houses cone-shaped rock formations called Hell’s Bells that measure up to six feet long.

But how did a member of this species of giant ground sloth — which scientists estimate to be around the size of a bear — end up at the bottom of a sinkhole? In a 2020 paper published in Historical Biology, paleontologists posited that the creature’s robust musculature may have allowed it to climb up steep cave walls.

It seems that X. oviceps, while not a swimmer, was a spelunker, possibly using the limestone caverns for shelter and as a water source. The researchers suggest that the specimen died before the cenote flooded, and the oxygen-poor waters helped preserve it. Without oxygen, microbes can’t break down a carcass as effectively or quickly, allowing the body to remain intact for ages as a biological time capsule.

Indeed, the researchers theorized that the sloth’s well-preserved skull, along with other skeletal fragments, is a consequence of the oxygen-poor environment in which it was fossilized. Beyond that, the specimen also helped demonstrate that X. oviceps likely used Mexico as a corridor to travel between North and South America as they spread from lower latitudes.

What Other Types of Prehistoric Sloths Have Scientists Found?

While subterranean sloths like X. oviceps may tower over today’s tree-dwelling sloths, they still pale in size to other species of giant ground sloths. The former is suspected to at least have been the size of a black bear, weighing around 500 pounds, but behemoths like Megatherium americanum tipped the scales at (literally) elephantine proportions, weighing more than 4.5 tons.

Megatherium Americanum

These massive beasts, native to South American steppes, could stand 12 feet tall. The giant sloth’s environment was home to an abundant supply of herbivores, which the omnivorous sloths likely hunted for food, dispatching their prey with seven-inch claws.

Thalassocnus

Other sloths, meanwhile, took to the sea. Enter Thalassocnus, an extinct group of semiaquatic sloths that mowed down meadows of seagrass during the Miocene and Pliocene eras, from roughly 16 to 2.5 million years ago. This would have put these shaggy prehistoric beasts alongside other aquatic titans like the megalodon, the largest predatory shark to have ever lived.

Other ground sloths employed strange defensive measures. Sloths from the Mylodontoidae family, a sister group to the Megatherium genus, possessed bony deposits in their skin called osteoderms. These structures are much more visible in their modern relatives, the armadillos, but in the ancient sloths they formed a subdermal layer of bony chainmail, which functioned as a resilient mesh that toughened their skin like armor.

What Happened to the Giant Ground Sloths?

In fact, there’s even some evidence that ancient humans in South America hunted down the sloths for their bony skin, furnishing the animal’s osteoderms into necklaces and other such ornaments. Unfortunately for the sloths, most were driven to extinction, possibly by a combination of hunting and climate change, around 10,000 years ago.

The last of the giant ground sloths died in what is now Cuba, where they persisted until around 2,500 B.C.E. This allowed them to coexist, at least briefly, with arriving humans. Still, the only living legacy of these giant creatures seems to be the six species of small, tree-dwelling sloths that can be found in South and Central America today.

At least, one would be inclined to assume that without a keen paleontological eye. Hundreds of tunnels dug into South American mud faces, the result of hours of labor thousands of years ago, are hypothesized to have come from giant sloths, or perhaps their armadillo brethren. These so-called paleoburrows are but one vestige of the influence large animals, termed megafauna, have had on environments.

While modern sloths may appear to be sleepy and unimpressive in comparison to these prehistoric titans, they have ultimately had the last laugh, managing to persist past all of their giant relatives. And as specimens like the sinkhole-exploring Xibalbaonyx demonstrate, their lineage is full of surprises.