On a bright, promising morning in the nation’s capital, President James A. Garfield walked briskly through the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, ready to escape the suffocating political humidity for a long-awaited summer vacation. It was July 2, 1881, only four months into his term, and the 20th President of the United States, a man who had pulled himself from impoverished obscurity to the highest office in the land, was buoyant, full of energy, and ready to introduce his two sons to his alma mater, Williams College. Flanked by Secretary of State James G. Blaine, Garfield represented the epitome of the American self-made man—a scholar, a Union General, and a brilliant orator whose very existence was a testament to meritocracy. He was, in short, a great hope for a nation still reeling from the bitter divisions of the Civil War and the corruption of the Gilded Age.

Then, the calm of the station was shattered. A delusional, failed lawyer and religious fanatic named Charles Julius Guiteau stepped forward, drew an ivory-handled .44 British Bulldog revolver—a weapon he had chosen specifically because he believed it would look impressive displayed in a museum—and fired twice into the President’s back.

Garfield collapsed, crying out, “My God, what is this?”

The immediate act was brutal, senseless, and horrifying. But what followed was not a swift, martyred passing. It was an 80-day living nightmare—a slow, agonizing public execution perpetrated not by the assassin, but by the very physicians sworn to save him. This tragedy remains one of the most overlooked yet profoundly consequential moments in American history, revealing a terrifying collision of political madness and deadly, entrenched medical ignorance that snuffed out a president and fundamentally altered the trajectory of the Republic. It is the story of how James A. Garfield was murdered twice: once by a bullet, and once by the unforgivable pride of 19th-century American medicine.

The Rise of a Reformer: From Canal Boy to Commander-in-Chief

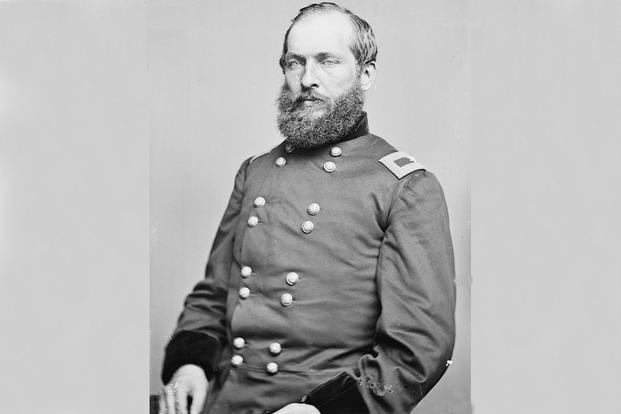

To understand the immensity of the tragedy, one must first grasp the extraordinary life of James Abram Garfield. Born in 1831 in a log cabin in Orange, Ohio, he was the last of the log-cabin presidents and the first to demonstrate calculus on a chalkboard. His path to the White House was a dazzling, improbable journey that cemented his image as a man of intellect and resilience.

He started life working on a canal boat, enduring malaria and grueling labor before dedicating himself to education. He excelled as a student, became a college president at a young age, and then, at the outbreak of the Civil War, answered the call to duty. His military service was exemplary; he rose to the rank of Major General, the youngest in the Union Army, and proved to be a capable and disciplined commander. After the war, he transitioned seamlessly into politics, serving nine terms in the House of Representatives, where he became known for his eloquence, deep moral conviction, and, crucially, his unwavering belief in civil service reform.

The late 1870s and early 1880s were dominated by the toxic political practice known as the Spoils System (or patronage), where government jobs were handed out not based on merit, but as rewards for political loyalty and campaign work. This practice had fostered incompetence, corruption, and bitter factionalism within the Republican Party, pitting the “Stalwarts” (who supported the status quo and former President Grant) against the “Half-Breeds” (who favored moderate reform, led by James G. Blaine).

Garfield, a genuinely unaligned dark-horse candidate, was thrust into the presidency at the contentious 1880 Republican National Convention, emerging on the 36th ballot as the compromise candidate. His victory, narrow but powerful, represented a mandate for change. He immediately tried to heal the party’s wounds, yet his subsequent moves—particularly his challenge to New York Stalwart Senator Roscoe Conkling over a plum patronage post—signaled his intent to dismantle the very system that had elevated many of his colleagues. He was a president ready to steer America toward professionalism and meritocracy, directly confronting the entrenched power structures of the Gilded Age.

This spirit of reform, this dedication to a cleaner, better government, was precisely what sealed his doom.

The Shadow of Madness: Charles Guiteau and the Spoils System

The man who lay in wait at the train station embodied the worst excesses of the patronage system. Charles Julius Guiteau was a walking, talking monument to narcissistic delusion. His life was a series of failures masked by an ever-growing sense of messianic importance.

He was a failed communal utopian at the Oneida Community, where other members derisively nicknamed him “Charles Gitout.” He was a failed theologian, plagiarizing his only book. He was a failed lawyer, arguing only one case (and losing it). Critically, he was a failed politician, convinced that the few times he delivered a slightly revised speech endorsing Garfield during the 1880 campaign were the single decisive factor in the election.

Guiteau arrived in Washington in 1881, demanding his reward: a prestigious consulship in Paris or Vienna. He was utterly unqualified and relentlessly annoying. He stalked the White House and the State Department, bombarding Secretary of State Blaine with letters. When Blaine finally exploded in frustration, telling Guiteau to never mention the Paris consulship again, the fragile ego of the assassin shattered.

Guiteau convinced himself that his rejection was not due to his incompetence, but was part of a larger, sinister plot by the Half-Breeds to destroy the Republican Party. His fractured mind concocted a divine mission: God told him to remove Garfield. He saw the assassination not as murder, but as a political necessity to elevate Stalwart Vice President Chester A. Arthur to the presidency. He believed Arthur, a Conkling acolyte, would be so grateful that he would reward Guiteau with the post he desired. This was the ultimate expression of the Spoils System’s toxicity—a delusional man believing the entire structure of government revolved around fulfilling his personal, narcissistic demand.

Guiteau purchased the British Bulldog revolver, practicing his aim and writing a chilling letter to General William Tecumseh Sherman, requesting protection after the deed. When he saw Garfield at the station, looking fit and vibrant, Guiteau carried out his “divine command,” firing the shots that brought down the President, and then coolly surrendering to police, proclaiming his identity as a Stalwart and declaring Arthur the new president.

The Death Blow: 19th-Century Medical Ignorance

The tragedy of James Garfield is that the bullet itself was not immediately fatal. The first shot merely grazed his shoulder. The second entered his lower back, passed the first lumbar vertebra, cracked a rib, and lodged behind his pancreas. It missed the spinal cord and all major arteries. Modern medicine confirms that with basic antiseptic care, Garfield would have likely been back on his feet within weeks.

But Garfield was struck in 1881—the heart of the Gilded Age, a period of rapid industrial and scientific growth, yet one where American medicine was tragically lagging behind. While European pioneers like Joseph Lister had already published groundbreaking work on antiseptic surgery and germ theory was gaining ground, the vast majority of American physicians, particularly the powerful elite in Washington, D.C., vehemently rejected the idea that invisible, microscopic organisms could cause disease. They adhered to older, more archaic theories of “morbid poisoning” and “miasma” (bad air).

The moment Garfield fell, the clock started ticking, not on the bullet, but on the massive infection about to be introduced.

The crisis was placed in the hands of Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (yes, ‘Doctor’ was his first name), the lead physician, a man whose arrogance was matched only by his complete denial of germ theory. In the cramped, filthy confines of the train station and later in the White House, the doctors initiated a horrific ritual. Driven by the misguided principle that the bullet must be found and removed to prevent “morbid poisoning,” a dozen or more physicians took turns plunging their fingers, often unwashed and still sticky from their morning rounds or even post-mortems, deep into the President’s wound.

They used instruments that were, at best, wiped clean, and at worst, still contaminated. The probing was relentless, invasive, and conducted without the benefit of anesthesia, as the doctors feared it might interfere with the diagnosis. Each dirty probe, each unsterilized surgical instrument, became a microscopic Trojan horse, carrying deadly streptococcus and staphylococcus bacteria directly into the President’s abdomen, transforming a simple, deep wound into a super-infected, pus-ridden catastrophe.

“He was suffering from a scorched fever, relentless chills, and increasing confusion,” wrote one contemporary historian. “The doctors tortured the president with more digital probing and many surgical attempts to widen the three-inch deep wound into a 20-inch-long incision, beginning at his ribs and extending to his groin. It soon became a super-infected, pus-ridden, gash of human flesh.”

Garfield’s condition became a painful, daily fluctuation between hope and despair, a public spectacle of agonizing deterioration. The sepsis, or blood poisoning, spread throughout his body. He wasted away from a healthy 210 pounds to a bony, skeletal 130 pounds. The nation watched, helpless, as their vibrant, promising President was slowly consumed from within.

The Humiliation of Alexander Graham Bell

As the summer progressed, the medical establishment grew desperate, but Dr. Bliss refused to acknowledge the fundamental error of their technique. Instead, the focus remained exclusively on locating the elusive piece of metal.

This desperation led to the involvement of one of the world’s greatest minds: Alexander Graham Bell. The inventor of the telephone had been working on a revolutionary device called the “induction balance”, a rudimentary metal detector. Bliss summoned Bell to the White House in the hope that his invention could save the President. Bell rushed to adapt the device to medical use.

The scene was one of tragic irony. Bell, an innovator dedicated to bringing the future to life, was trying to save a patient trapped by the past. Yet, even this final, ingenious attempt was sabotaged by the same stubborn arrogance that had doomed the President from the start.

Dr. Bliss had publicly declared, with characteristic certainty, that the bullet was lodged on the right side of Garfield’s body. When Bell arrived, Bliss, fearing professional embarrassment, rigidly insisted that Bell only scan the right side. Furthermore, unbeknownst to Bell, Garfield had been moved onto a new mattress containing a rare, cutting-edge feature for the era: metal springs.

When Bell passed the induction balance over the President’s body, the device registered metal everywhere—the springs in the bed created overwhelming static, rendering the results meaningless. A subsequent, accurate attempt by Bell when the President was briefly moved off the bed was again suppressed by Bliss, who preferred to cling to his flawed theory and his faulty diagnostic spot. The bullet, the autopsy later revealed, was actually safely encased and walled off behind the pancreas, resting on the left side of his body—exactly where Dr. Bliss had forbidden Bell to look.

The Final Vigil and a Legacy Forged in Pain

As the Washington summer heat became unbearable, the nation rallied around its suffering leader. Engineers constructed a massive, complex cooling system using thousands of pounds of ice in a basement chamber and a fan system to circulate chilled air through the White House—an early, innovative form of air conditioning. This attempt to ease the President’s fever, however, was only a temporary respite. The infection was too widespread.

In a last, poignant effort to give Garfield a final chance at recovery, the nation’s railroad companies cooperated to build a special, temporary spur line directly to the seaside mansion of his friend, Judge Joseph Hilton, in Elberon, New Jersey. The President, accompanied by his devoted wife Lucretia, made the final, symbolic journey. Lucretia, affectionately known as “Crete,” had been a pillar of strength throughout the ordeal, often taking the role of chief nurse and demanding better care for her husband.

For a few days, the sea air seemed to revive him, offering the nation a fleeting moment of hope. But it was only the final flame before the wick extinguished. On the evening of September 19, 1881, Garfield suffered a massive hemorrhage and heart attack. His final breaths were accompanied by the desperate cry, “This pain, this pain!” He died at 10:35 p.m., just two days short of two months since the shooting.

The national outpouring of grief was immense and prolonged. James A. Garfield became a martyr for a cause he had championed but never lived to see enacted.

The Truth of the Killer and the Birth of Reform

Meanwhile, the man responsible for the initial violence sat in jail, reveling in the attention and preparing for his trial. Charles Guiteau was a spectacle in the courtroom, dancing, reciting poetry, insulting the jury, and proclaiming his divine mandate.

In a moment of breathtaking audacity, Guiteau defended himself by arguing that the doctors, not he, were the true murderers. “I merely shot the President,” he stated chillingly. “The doctors did that.”

The sheer chutzpah of the argument—the assassin blaming his victim’s healers—was staggering, yet tragically, he was technically correct. The autopsy confirmed that the bullet had not caused the death; the widespread infection, the abscesses caused by the unsterile probing, and the massive hemorrhage resulting from those abscesses were the culprits.

Despite the medical evidence supporting Guiteau’s claim of malpractice, the jury was unmoved by his plea of insanity. The public demanded retribution, and they wanted a guilty verdict. Guiteau was convicted of murder and, on June 30, 1882, he was executed by hanging, shouting a final poem as he dropped.

The true legacy of Garfield’s death, however, lay in its political seismic shift. The narrative that a president was killed by a disappointed office seeker highlighted the utter rot at the core of the Spoils System. Garfield’s tragic 80-day struggle served as the moral impetus needed to drive reform forward.

In his memory, President Chester A. Arthur, the very man Guiteau had intended to elevate, astonishingly transformed himself from a Stalwart beneficiary of patronage into a champion of reform. On January 16, 1883, President Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act into law. This landmark legislation established the Civil Service Commission and mandated that many government jobs be filled based on merit exams rather than political favors. It was the beginning of the end for the toxic patronage that had defined American politics for decades.

James A. Garfield died as the forgotten martyr of two crucial wars: the war against political corruption and the war against scientific ignorance. His death was a horrifying, drawn-out advertisement for the necessity of both Listerian antiseptic methods in medicine and merit-based governance in politics. He was a man of the future, doomed by the medieval practices of his own time, and his agonizing sacrifice remains a profound, emotionally charged chapter in the story of the Republic he died to save. The story of Garfield is a timeless reminder that sometimes, the greatest dangers are not the obvious villains with guns, but the unseen errors propagated by well-meaning but tragically arrogant authority.