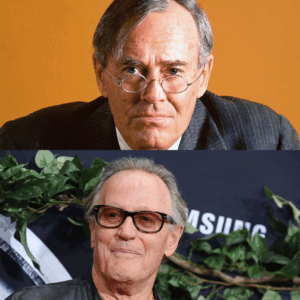

Once, they were brothers in spirit, united by a shared vision that would change the course of American cinema. Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda didn’t just star in Easy Rider; they embodied the restless, rebellious heart of a generation disillusioned with the status quo. Their 1969 masterpiece captured the spirit of freedom and the bitter taste of disillusionment, catapulting them into the pantheon of Hollywood legends. Yet, behind the scenes, that partnership was a battlefield. What began as a bond built on trust and shared dreams crumbled under the weight of ego, addiction, and years of corrosive, unresolved pain.

The feud between these two icons raged for decades, a silent, vicious war that ended, not in peace, but in a final, heartbreaking act of defiance. When Dennis Hopper passed away fifteen years ago, his last wish was to ensure Peter Fonda was banned from his funeral. In a moment that stunned onlookers and fueled the haunting question of what truly transpired between them, Fonda defied the dying man’s command and showed up anyway. This is the tragic, untold story of two legends who called each other family, the chaos that consumed them, and the ultimate act of unforgiveness that sealed their painful legacy.

The Rebel Who Was Cursed by Hollywood

Dennis Hopper was born in Dodge City, Kansas, in 1936, a fitting birthplace for a man who would become the ultimate embodiment of restless American rebellion. A restless soul from the start, his passion for performance led him to New York’s prestigious Actor’s Studio, where he befriended the likes of Vincent Price and honed the fearless, almost manic, intensity that defined his career.

His breakout arrived early with an unforgettable, albeit small, role in James Dean’s classic, Rebel Without a Cause. It was on that set that he met a spirited 16-year-old Natalie Wood, sparking a brief, electric connection that would linger forever in his memory.

But Hopper’s fiery spirit soon clashed with the rigid authority of old Hollywood. His role in the 1957 film From Hell to Texas should have been his breakthrough, but it became a career-killing battlefield. He clashed repeatedly with the powerful director, Henry Hathaway, culminating in an instance where Hopper stubbornly re-shot a single scene over eighty times. In a moment of cold finality, Hathaway delivered a line that became a self-fulfilling prophecy for the young actor: “Kid, there’s one thing I can promise you: you’ll never work in this town again.”

Hathaway’s curse held true for nearly a decade. Exiled from the studio system, Hopper was officially blacklisted, his reputation for chaos and defiance making him impossible to hire. Yet, this exile didn’t destroy him; it incubated him.

The Abyss of the Hollywood Hills Commune

For a brief, tumultuous period, love seemed to offer a chance at stability. Hopper married actress Brooke Hayward, a childhood friend of Jane Fonda, in a chaotic, unsanctioned union that enraged her powerful Hollywood father, Leland Hayward. Ignoring the disapproval, they eloped, and for a short while, they shared a genuine passion for art and freedom, welcoming a daughter, Marin.

But Hopper’s self-destructive impulses never truly rested. By the mid-1960s, his Hollywood Hills home had become the epicenter of the counterculture, a wild, chaotic commune fueled by art, music, and an alarming torrent of drugs and alcohol. What began as creative rebellion quickly devolved into a nightmare. Hopper’s drinking spiraled out of control, his stepson recalling the stench of alcohol clinging to him constantly. His temper became unpredictable, often buried beneath rage and paranoia.

The violence became domestic. One night, after Brooke refused to make him dinner, Hopper came home drunk and furious, threatening her life in front of their children. Terrorized, Brooke fled with the kids and filed for divorce and a restraining order, ending a marriage that had become unbearable. Hopper’s obsession with guns and the palpable, ever-present chaos—with Hell’s Angels often asleep on the living room floor—confirmed that he was disappearing behind a wall of addiction and anger.

The Genesis and Madness of Easy Rider

It was out of this wreckage, amid the shattered bottles and broken trust, that something extraordinary began to brew. Exiled and running out of options, Hopper joined forces with Peter Fonda and writer Terry Southern to create an independent, raw vision that broke all the rules. The project was Easy Rider, but the road to filming was a war zone of ego and madness.

Hopper’s volatility was evident even before filming began. Actor Rip Torn, initially cast as George Hansen, walked off the project after Hopper reportedly pulled a knife during a heated meeting. The role was eventually given to an unknown Jack Nicholson, a twist of fate that would launch Nicholson’s legendary career.

Once filming started, art and addiction became indistinguishable. Hopper, Fonda, and Nicholson didn’t just act their drug-fueled scenes; they lived them, blurring the line between performance and self-destruction. Hopper drank constantly, raging one moment and collapsing in tears the next. Bottles were smashed and tempers flared, his mind teetering on the edge of brilliance and total breakdown.

When Easy Rider exploded onto the cultural scene, it was hailed as the anthem of a generation. Hopper became the new rebel genius, the face of defiance. But beneath the applause, his old demons—now fed by fame and fear—were waiting, stronger than ever.

The Fall Into Oblivion

The triumph of Easy Rider should have been his redemption, but instead, it set him on a darker path. Flushed with success, he was given $1 million to direct his dream project, The Last Movie, filmed high in the Peruvian mountains. It swiftly descended into a hallucinatory nightmare of drugs and ego. The set became indistinguishable from Hopper’s own unraveling mind, and the subsequent documentary, The American Dreamer, only solidified the public’s view of a man flirting with oblivion, wandering naked through his New Mexico commune, obsessing over guns and paranoia.

The reckless stunts followed. By 1983, his obsession with self-destruction became terrifyingly literal when he attempted the notorious Russian dynamite death chair—sitting on a chair packed with explosives and lighting the fuse. Against all odds, the showman survived, but the act exposed a man desperately trying to outrun his own sanity.

The absolute rock-bottom came later that same year. While filming Jungle Warriors in Mexico, crew members found him stumbling naked through a small village, disoriented and muttering to himself. He was fired and shoved onto a flight home, but the nightmare continued mid-journey when Hopper tried to climb out onto the plane’s wing, convinced he could somehow escape. Passengers screamed as the crew restrained him.

That horrifying flight—a man reduced to trying to fly away from his own body—marked the end of his long, bloody war with the bottle. In 1983, Dennis Hopper finally quit drinking, not out of strength, but because he had literally run out of places to fall.

The Final, Vicious Courtroom War

The years that followed were marked by brief, chaotic relationships, including an impulsive, nine-day marriage to Michelle Phillips of The Mamas and the Papas. It wasn’t until 1996, when he married Victoria Duffy, that he seemed to find a semblance of domestic calm, welcoming a daughter, Galen, in 2003. For a decade, the Hollywood rebel looked almost content.

But fate was not finished. In 2009, Hopper was diagnosed with prostate cancer, which rapidly spread to his bones. By early 2010, his body was frail, his movements slow and painful. He knew the end was near, yet in those final months, one last, brutal storm erupted—a divorce war with Duffy.

In one of his last acts, the dying actor fought savagely to limit his wife’s inheritance, tried to have her removed from their beloved beach house, and filed for a restraining order. He accused her of “outrageous conduct,” publicly calling her “insane, inhuman, and volatile.” After fourteen years together, the marriage that had once seemed like his redemption turned into a devastating courtroom spectacle that raged right up until his final moments.

The Unforgiven: Peter Fonda and the Ashes

Dennis Hopper passed away in May 2010, leaving behind a filmography of over 100 movies. His life was a turbulent odyssey of genius and ruin, but even in death, his bitterness toward Peter Fonda refused to rest.

The creative partnership on Easy Rider had turned toxic due to jealousy and ego, primarily over control and a subsequent legal war over Fonda’s residual profits. The wounds ran so deep that when Hopper’s health failed, he made the final, shocking decision: Peter Fonda was explicitly banned from his funeral.

Despite the hostility, Fonda still tried to pay his respects, a final gesture of a friendship that had once defined a generation. But Hopper’s family, honoring the absolute finality of his wish, turned Fonda away at the door. It was a chilling, sorrowful end to a bond that began in a blaze of glory and concluded in the icy silence of unforgiveness.

The final word on Hopper’s legacy of chaos came from an anecdote that perfectly encapsulated his recklessness. At the height of his addiction, not long after Easy Rider, he was in a studio office when he saw a bowl of white powder. Mistaking it for cocaine, he casually snorted it. Moments later, he discovered the terrifying, horrifying truth: it wasn’t drugs, but the cremated ashes of an executive’s late wife. That single, shocking act—a man forever consumed by rebellion and destruction, even accidentally consuming the remains of a stranger—sums up everything about Dennis Hopper: a brilliant, broken artist who lived without limits and ultimately paid the ultimate price for his own magnificent, chaotic making.