The Future of Speed is Here, and It’s Brutal

The world of Formula 1 is never static. While fans cheer for the overtakes on Sunday, the real race happens years in advance, inside the glowing monitors of supercomputers and the hushed wind tunnels of Silverstone and Maranello. The 2026 regulation changes promise to be one of the most significant shake-ups in the sport’s history, forcing teams to completely rethink how a car cuts through the air. Thanks to a fascinating collaboration between B Sport, Airshaper, and talented designers Emil and Hugo, we don’t have to wait until 2026 to see the future.

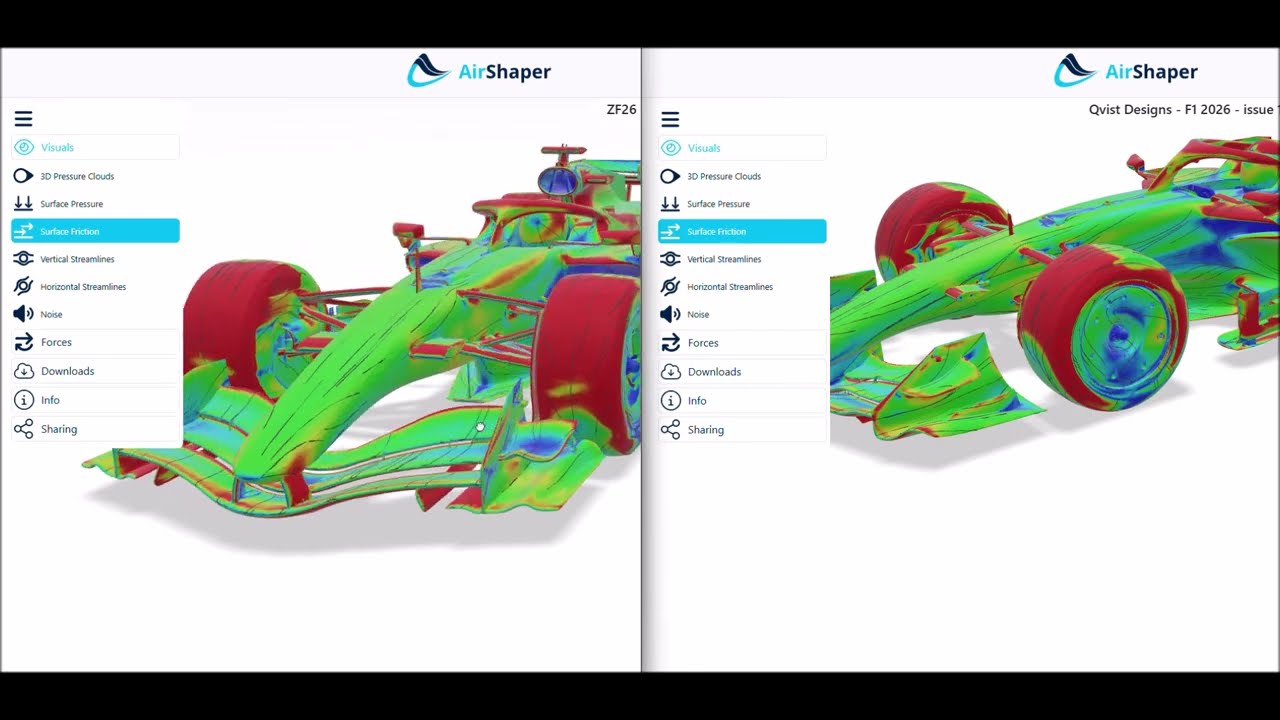

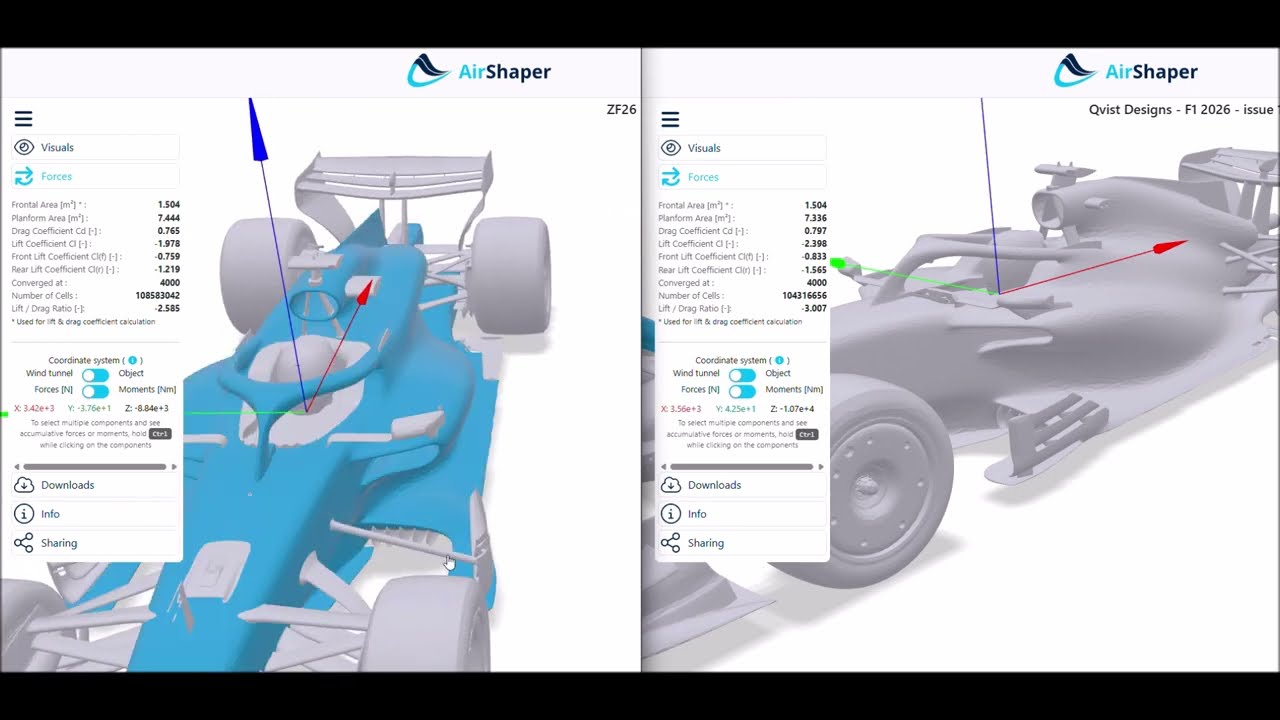

We have been granted an exclusive look into the “invisible war” of aerodynamics—a comparison of two distinct 2026 car concepts analyzed with over 100 million simulation cells. The results are startling, proving that in Formula 1, a millimeter of carbon fiber is the difference between a champion and a backmarker.

The Shrinking Beast: A New Silhouette

The first thing that strikes you about the 2026 generation is the size. For years, drivers and fans alike have complained about “boat-like” cars that are too wide to race wheel-to-wheel on historic tracks like Monaco. The new regulations address this head-on. As the simulations load, the frontal area comparison confirms it: the 2026 machines are significantly narrower than their predecessors.

However, a smaller target doesn’t mean an easier job for the air. In fact, shrinking the car compresses the aerodynamic challenges, forcing designers to be even more clever with how they manipulate the fluid dynamics around the chassis. Our two contenders, concepts by designers Emil and Hugo, offer two radically different philosophies on how to tackle this new rulebook.

The Front Wing: The First Line of Defense

Aerodynamics is a domino effect. What happens at the tip of the nose dictates the performance of the entire car. If you mess up the airflow at the front wing, you can’t fix it at the back. This is where the battle lines are drawn.

Hugo’s model features a front wing with long stalks and an aggressive flap design. To the naked eye, it looks fast. But the CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) pressure maps reveal a harsh truth. The simulations show “red” high-pressure zones where they shouldn’t be and devastating “blue” separation pockets on the second element. The flow essentially “stalls”—it gives up and detaches from the wing surface halfway through. In racing terms? That’s massive performance left on the table.

Contrast this with Emil’s design. His front wing features shorter stalks and a cleaner, less aggressive angle. The result is a sea of blue on the underside pressure map, indicating smooth, attached airflow. It’s efficient, effective, and crucial for feeding clean air to the rest of the car. It’s a masterclass in the “less is more” philosophy.

The Suspension and Sensor Dilemma

One of the most interesting technical divergences is the suspension. Emil has opted for a “push-rod” geometry, while Hugo has gone for a “pull-rod” system. Each has mechanical benefits, but aerodynamically, they act as flow conditioners.

But the devil is in the details—specifically, the tiny ones. On Hugo’s model, a small tire temperature sensor, a mandatory piece of equipment, is slightly misaligned with the incoming airflow. You might think, “It’s just a sensor, who cares?” The air cares. The simulation highlights a nasty separation bubble forming right behind the sensor. This turbulent “dirty air” cascades downstream, disrupting the sidepods and floor edges. It’s a sobering reminder that in F1, you cannot overlook anything.

The Sidepod & Floor War

Moving to the middle of the car, we see the sidepods—the area that defined the current ground-effect era (think of Mercedes’ “zero-pod” vs. Red Bull’s undercut).

Both concepts struggle here, proving just how difficult the 2026 regulations will be. Hugo’s car features massive cooling inlets, while Emil’s are more compact. Yet, both designs suffer from airflow separation along the outer edges. The air struggles to cling to the steep curves of the bodywork, creating drag and turbulence.

The most fascinating skirmish, however, is happening on the floorboards. The regulations allow for a metal “stay”—a support rod to stiffen the floor. Hugo’s design utilizes this stay, which allows the floor to be lighter and use less material. It sounds like a smart weight-saving hack.

But aerodynamics is a cruel mistress. The simulation reveals that this thin metal rod acts like a rock in a stream. It creates a wake of turbulence that disrupts the crucial “undercut” area, robbing the rear of clean air. Emil’s design skips the stay, likely resulting in a heavier floor, but the airflow is significantly cleaner. It’s the classic F1 trade-off: do you want a lighter car or a more aerodynamic one? The answer usually lies in the stopwatch.

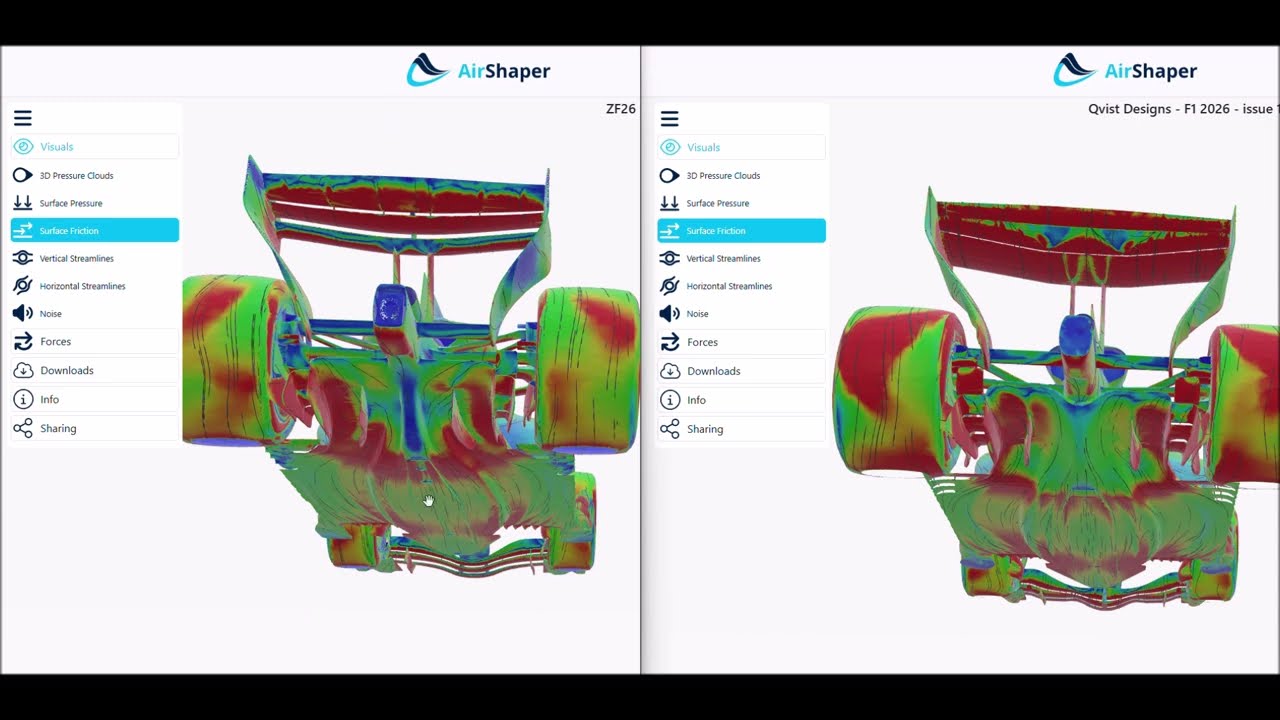

The Rear Wing: Escaping the Wake

The back of the car is where the “downforce” checks are cashed. If the air arriving here is messy, the rear wing can’t do its job.

Hugo’s rear wing concept runs into a major issue identified by the simulation: it sits directly in the line of fire of the “wake” generated by the front wheels. The turbulent, low-energy air thrown up by the front tires hits the rear wing in a straight line. This renders parts of the wing ineffective, drastically reducing rear grip—a nightmare for drivers trying to put power down out of corners.

Emil’s design, on the other hand, manages to route this dirty wake outboard, away from the rear wing elements. His wing sits in relatively “clean” air, allowing the flaps to generate maximum suction. Furthermore, his flap design—one large main plane with two smaller flaps—proves far more efficient than Hugo’s multi-element approach, which suffers from flow separation due to overly long chord lengths.

The Verdict: Precision Wins

This deep dive into 2026 simulations isn’t just about picking a winner between two digital models. It’s a window into the headache that Adrian Newey, James Allison, and every other F1 technical director is currently facing.

The simulations by Airshaper and B Sport demonstrate that 2026 won’t just be about who has the most powerful engine. It will be a war of refinement. It will be about aligning a sensor by two millimeters to prevent a separation bubble. It will be about deciding if a 500-gram metal stay is worth the aerodynamic penalty.

As we look toward the future, one thing is clear: the cars are getting smaller, but the challenge is getting bigger. If these simulations are any indication, the 2026 grid will be defined by those who master the invisible art of airflow, and punished by those who miss the details.