The Unlikely Hero of Automotive History

In the high-stakes world of automotive engineering, we often look to the titans of luxury—the German giants like Audi, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW—for the trickle-down technology that eventually makes our daily commutes safer and smoother. We assume that innovation flows from the top down, from the six-figure super-sedans to the budget-friendly hatchbacks. But history, as it turns out, has a funny way of flipping the script.

Sometimes, the revolution doesn’t start in a pristine laboratory in Stuttgart or Munich. Sometimes, it starts with a blank sheet of paper, a tight budget, and a mandate to build a car for everyone. This is the story of how the 1993 Ford Mondeo, a car designed for school runs and grocery getting, pioneered a suspension system so brilliant that the world’s most prestigious manufacturers had no choice but to copy it.

The “World Car” Challenge

Rewind to the early 1990s. Ford was facing a massive challenge. They needed to replace the aging Sierra, a rear-wheel-drive staple that had served them well but was becoming obsolete. The goal was ambitious: create a “World Car.” This vehicle needed to succeed in every market, from the winding roads of Europe to the highways of America. They named it the Mondeo, derived from Mundus, the Latin word for “world.”

The engineers were given a trifecta of priorities that usually don’t mix: maximum interior space, sleek design, and class-leading handling. To achieve the interior space, they utilized a “Cab Forward” design, pushing the windshield forward and shortening the hood. This necessitated a transverse engine layout (where the engine sits sideways), driving the front wheels.

However, the real headache was the rear. To make an estate (wagon) version that could actually haul cargo, they needed a suspension system that was incredibly compact. It couldn’t intrude into the trunk space. Yet, to meet the handling goals, it had to be fully independent, offering precise control over camber and toe angles. And, being a Ford, it had to be cheap to manufacture.

The “Genius” Solution

What the Ford engineers came up with was nothing short of a mechanical masterpiece. They designed a multi-link rear suspension that defied the conventions of the time.

The setup involved two long trailing arms to handle the longitudinal loads, acting as the sturdy backbone of the system. They then added three transverse links: a small lower wishbone, an adjustable upper wishbone (perfect for fine-tuning camber), and a crucial fourth arm—the “Control Blade”—positioned rearward to manage the toe angle.

The stroke of genius was the separation of the spring and the damper. By moving the spring to the rearward arm and positioning the slim damper vertically, they maximized trunk space without sacrificing performance. It was a “best of both worlds” scenario: the compactness of a primitive beam axle with the sophistication of a fully independent system. It was cheap, welded from simple sheet metal, yet it offered lateral support and kinematic accuracy that rivaled expensive sports cars.

The Focus Revolution and the “Copycat” Era

When Ford ported this design over to the first-generation Focus, the difference was night and day. The Focus didn’t just drive well for a cheap car; it drove better than cars twice its price. Its main rivals, the Volkswagen Golf and the Opel Astra, were still using a “Twist Beam” rear axle—essentially a single piece of metal connecting the rear wheels. While cheap and durable, the twist beam meant that if one wheel hit a pothole, the other wheel felt it too. It was unrefined and lacked precision.

The Ford Focus, with its fancy “Control Blade” multi-link rear, felt planted, agile, and premium. It was a wake-up call that sent shockwaves through the industry. Drivers and journalists raved about the handling, and the sales numbers followed.

Volkswagen, realizing they had been outmaneuvered, didn’t just tweak their design; they seemingly traced Ford’s homework. When the PQ35 platform (which underpinned the Golf Mk5) arrived, it featured a rear suspension layout that was virtually identical to Ford’s. The “Control Blade” concept was no longer just a Ford secret; it became the industry standard.

A Legacy That Transcended Brands

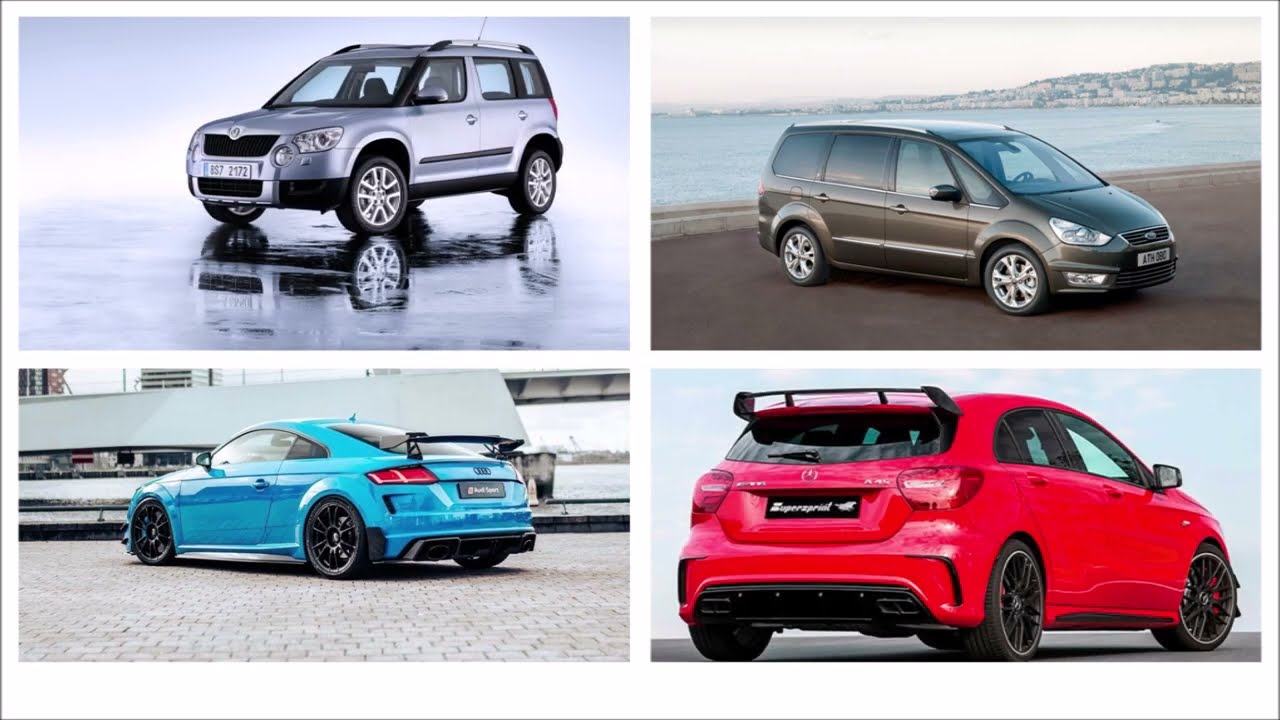

The ripple effect was massive. The Volkswagen Group began using this copied design across their entire lineup for transverse-engine cars. From the humble Golf to the sporty Audi A3 and even the high-performance Audi S1, the DNA of the 1993 Mondeo was there, keeping the tires glued to the road.

It wasn’t just the Germans. Because Ford owned Volvo and Mazda at the time, the technology spread there too. The Mazda 3, Mazda 6, and Volvo V50 all benefited from this shared wisdom. Even Toyota, a company known for its conservative engineering, eventually adopted the design for its “New Global Architecture” in 2018. When Mercedes-Benz redesigned the A-Class to finally handle like a proper luxury car, guess which layout they chose?

The End of an Era

It is a testament to the original design’s brilliance that it remained relevant for over three decades. Different manufacturers made small tweaks—Mercedes used aluminum for weight savings, Opel added a “Watt’s Linkage” to their beam axles before eventually capitulating—but the core concept remained the same.

Today, the story comes to a bittersweet close. Ford has moved on to newer, more complex multi-link designs for better comfort, and the production of the Mondeo and Focus has largely ceased as the world shifts toward SUVs and electric vehicles.

But the next time you see a sharp-handling hatchback or a compact crossover carving up a corner, remember the unsung hero. It wasn’t born on a racetrack or in a luxury boutique. It was born on a Ford assembly line in the 90s, proving that sometimes, the smartest engineering is simply about solving a problem that everyone else ignored. The Mondeo may be gone, but its genius rides on.