In the high-octane pantheon of Formula 1, immortality is usually purchased with silverware. We remember the names etched onto trophies, the drivers who stacked points like bricks to build empires of statistics. Yet, there is a ghost in the machine—a name that defies this cold logic, hovering above the sport with a reverence that dwarfs many multi-time champions. Gilles Villeneuve.

Ask a die-hard fan why they remember the small French-Canadian with the heavy right foot, and they won’t recite numbers. They will tell you about a Ferrari going sideways in the rain, tires smoking in a defiant ballet. They will speak of impossible overtakes and a refusal to lift off the throttle even when survival instincts screamed otherwise. But at the center of this romantic legacy lies an uncomfortable, jagged question: If Gilles Villeneuve was truly this fast, this fearless, and this respected, why does his name not appear on the list of World Champions?

For decades, the easy answers have served as comforting balms. We blame bad luck. We blame the mechanical frailty of his cars. We blame the inherent danger of an era that claimed too many sons. But these answers are incomplete. They are the lazy explanations of a sport trying to hide its own nature. The truth, as revealed by three of the sport’s most cerebral titans—Niki Lauda, Jackie Stewart, and Alain Prost—is far more complex and deeply human. Villeneuve didn’t just fail to win a title; he fundamentally collided with the very logic of Formula 1.

The Cold Mathematics of Niki Lauda

To understand the first layer of this tragedy, we must look through the eyes of Niki Lauda, a man who viewed racing not as a passion play, but as a solvable equation. Lauda, a three-time champion, never spoke of Villeneuve’s lack of a title in emotional terms. To him, the issue was structural.

Lauda’s philosophy was brutal in its simplicity: a championship is an exercise in accumulation. It is about controlling the chaos of a season, extracting maximum points when the car is good, and—crucially—minimizing damage when it is not. It requires a driver to hold two contradictory thoughts in their head: the desire to win today, and the discipline to accept third place for the sake of tomorrow.

This was the antithesis of Gilles Villeneuve. The Canadian did not drive with a calculator in the cockpit. He drove with a sledgehammer. Whether he was fighting for the lead or scrapping for sixth place, his intensity remained at a fever pitch. He refused to dilute his attack based on the trivialities of tire degradation or championship standings.

Lauda observed that Villeneuve treated every single Grand Prix as if it were the final, decisive battle of a war. When that mentality works, it produces magic—like his heroic victory at the 1981 Monaco Grand Prix, dragging an unwieldy turbocharged Ferrari around the tight streets purely on will. But across a season, that magic creates exposure. It leads to mechanical failures born of sustained overdriving. It turns potential podiums into retirements.

In Lauda’s cold analysis, Villeneuve’s “failure” was actually a refusal to accept the difference between race-winning talent and championship sustainability. A world champion must know when not to attack. Villeneuve viewed such restraint as a form of dishonesty.

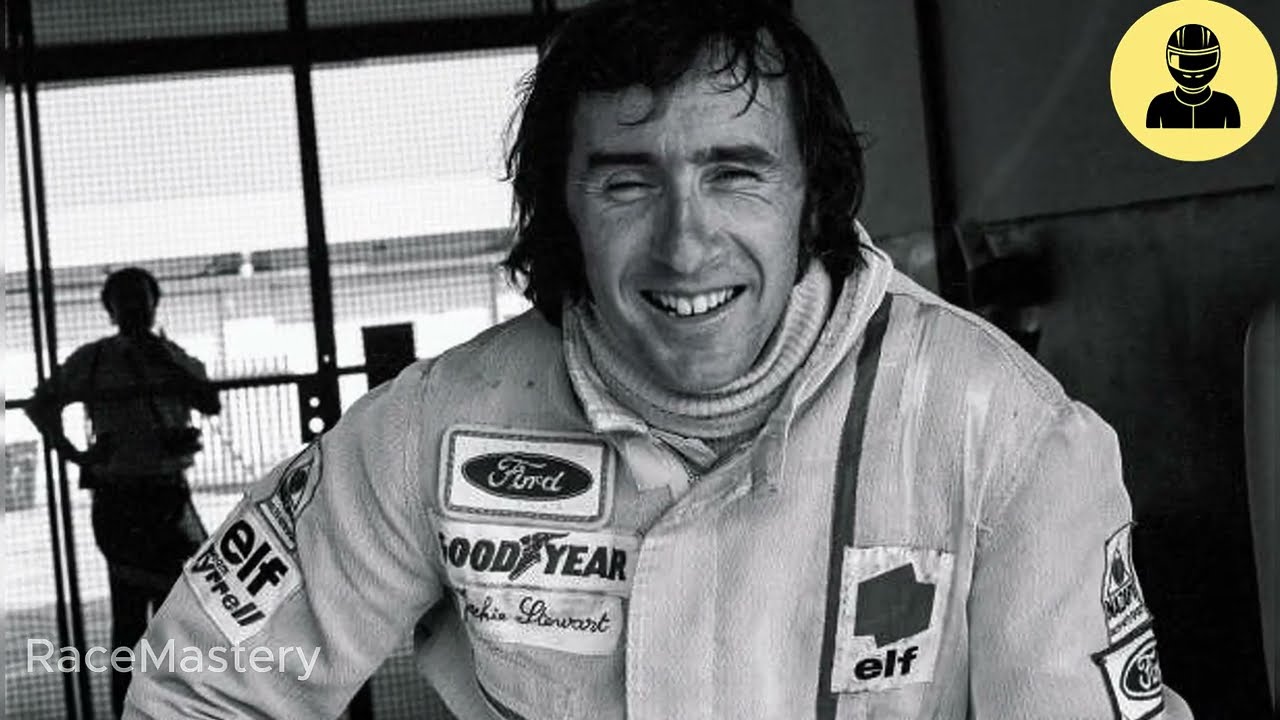

The Safety Paradox of Jackie Stewart

If Lauda’s critique was mathematical, Sir Jackie Stewart’s was an urgent, flashing warning light. Stewart, the crusader who dragged F1 kicking and screaming into the era of safety, looked at Villeneuve and saw a tragedy waiting to happen. He didn’t question Gilles’ talent; he questioned the system that exploited it.

Stewart raced in an era where the cost of a mistake was often death. He spent his career building barriers—both physical and metaphorical—to keep drivers alive. When he watched Villeneuve in the late 70s and early 80s, he saw a driver who habitually raced beyond the limits of his machinery. He saw a man sliding a fragile car on worn tires, keeping the throttle pinned when physics suggested otherwise.

To the fans and the teams, this was heroism. It was the spectacle they paid to see. But to Stewart, it was a systemic failure. Formula 1 at the time offered no structural restraint. The cars were brittle, the tracks were unforgiving death traps, and yet the culture encouraged drivers to push because “pushing” sold the narrative of the brave gladiator.

Villeneuve gave the sport exactly what it craved: commitment without calculation. But Stewart argued that a driver with such raw, unbridled instincts required boundaries. He needed a team or a mentor to rein him in, to teach him the art of survival. Instead, the paddock applauded every time he exceeded a limit.

From this perspective, Villeneuve was denied a championship not by his rivals, but by a lack of longevity. A driver cannot mature into a world champion if the sport does not allow him to survive his own learning curve. The very qualities that made him a legend—his absolute refusal to acknowledge fear—placed him in an environment that was all too happy to consume him.

The Philosophical Choice of Alain Prost

Perhaps the deepest cut comes from “The Professor,” Alain Prost. If Lauda spoke of math and Stewart of safety, Prost spoke of philosophy. His explanation reveals that Villeneuve’s lack of a title was, in many ways, a conscious choice.

Prost built his four-championship career on the belief that restraint is a weapon. He understood that you could lose a battle to win the war. He was willing to let a rival pass him if fighting back meant risking a DNF (Did Not Finish). To Prost, this was intelligence. To Villeneuve, it was betrayal.

Villeneuve raced according to a strict internal code of honor. If there was a gap, he went for it. If there was a fight, he engaged. To back out of a duel for “strategic reasons” felt wrong to him, like a violation of the spirit of racing. Where Prost saw patience, Villeneuve saw surrender.

This fundamental difference is why Villeneuve was so beloved by fans and so loyal to Ferrari. He possessed a purity that the “smart” drivers lacked. He didn’t want to win by accumulation; he wanted to win by being true to his identity as a racer. He wanted to beat you on the track, wheel-to-wheel, every single time.

Prost admired this. He respected the purity of it. But he also recognized that it was incompatible with the way championships are actually won. To lift the trophy, a driver must be able to separate their pride from the outcome. They must accept that a lesser result today secures the glory of tomorrow. Villeneuve never made that separation. He refused to compromise his racing soul for the sake of a points table.

The Uncomfortable Conclusion

When you layer these three perspectives—Lauda’s logic, Stewart’s concern, and Prost’s philosophy—a clear and poignant picture emerges. Gilles Villeneuve did not miss out on a World Championship because of a singular flaw or a stroke of bad luck. He missed it because he was fighting a war on three fronts against the very nature of Formula 1.

He was a poet in a room of accountants, a gladiator in a game of chess. Lauda showed us he couldn’t manage the math. Stewart showed us the environment failed to protect him. Prost showed us he refused to accept the compromises required to win.

None of this diminishes him. In fact, it elevates him to a plane that no trophy can reach. Formula 1 has crowned many champions who adapted themselves to the system, who learned to play the game of points and percentages. Gilles Villeneuve asked the system to adapt to him—to his honor, his commitment, and his terrifying authenticity.

The system never did. And that is why his legacy feels so different. Trophies are just metal; they measure success. Gilles Villeneuve measured truth. He raced exactly as he believed racing should be done, even when it worked against him. He never became World Champion, but he became something far rarer and more enduring: a reminder that true greatness is not always found at the top of the standings, but in the courage to race without compromise.