Formula 1 is never just about the drivers; it is a high-stakes chess match played at 200 miles per hour, where the pieces are made of carbon fiber and the board is defined by a dense book of technical regulations. As the sport hurtles toward the seismic shift of the 2026 regulation overhaul, a new battleground has emerged. Buried within the dense legalese of the FIA’s new technical statutes are opportunities—tiny, geometric cracks in the rulebook that the world’s smartest aerodynamicists are already prying open.

Recent insights into the design process for the 2026 rear wing and floorboard have revealed not just how the new cars will look, but how they will dominate the air around them. From a “shadowing” loophole that could allow forbidden shapes to hide in plain sight, to a radical rethinking of active aerodynamics, the 2026 grid is shaping up to be far more complex than the “simplified” rules intended.

The Return of the Bargeboard Spirit

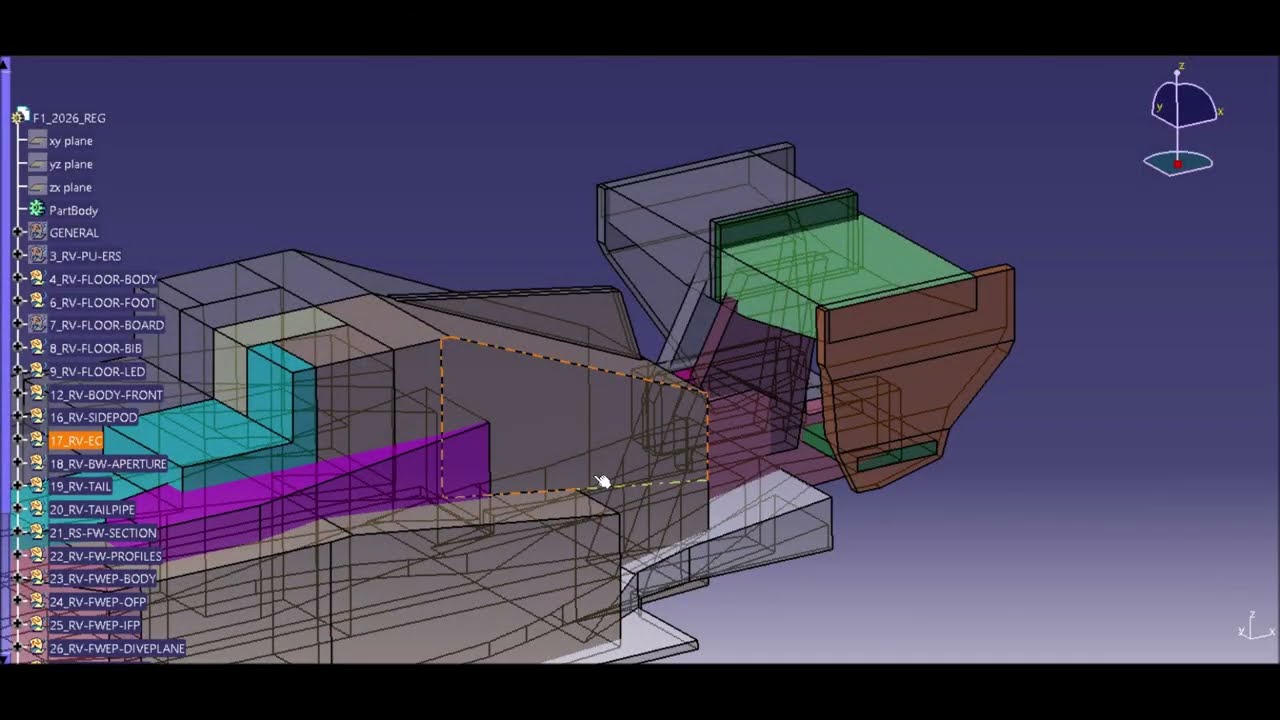

One of the most striking developments in the preliminary 2026 designs is the evolution of the floorboard. For years, the FIA has tried to clean up the area behind the front wheels—the “bargeboard” area—which famously became a messy thicket of winglets and turning vanes prior to 2022. The goal was to reduce “dirty air” and improve overtaking. However, you cannot unlearn physics, and engineers are finding ways to bring back the performance benefits of those old designs within the new constraints.

The latest design concepts utilize the area ahead of the 825mm mark to introduce a radical new structure: a freely designed “outwashing” first element followed by three upwashing horizontal elements. While this sounds like technical jargon, its function is aggressive and decisive. By carefully angling these elements within the legal 15-degree limit and adhering to the three-section rule, designers can effectively trap air in front of the sidepod.

This trapped air creates a high-pressure zone specifically positioned behind the front wheel. In the world of aerodynamics, pressure is a tool. By manipulating this high-pressure zone, teams can push the turbulent “wake” generated by the rotating front tires outboard—away from the car’s floor and rear wing. This is the holy grail of F1 aerodynamics: sealing the floor and ensuring clean air flows to the rear of the car. It is a sophisticated, legal workaround that mimics the function of the banned bargeboards, proving that in F1, concepts never truly die; they just evolve.

The Rear Wing Revolution: Article 3.11

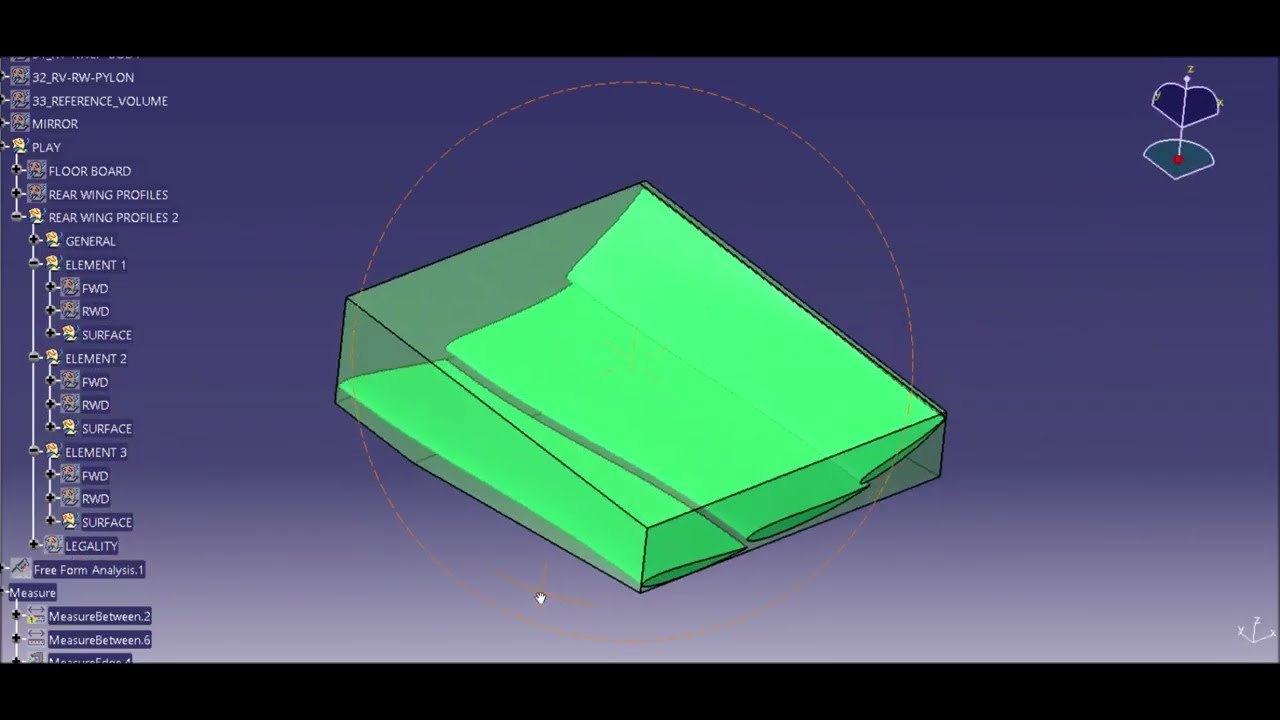

The most visually dominant change for 2026, however, is the rear wing. Governed by Article 3.11 of the technical regulations, the new rear wing is a three-element assembly that must fit within a strict “reference volume” box. On the surface, it seems restrictive. Teams must position up to three elements, connect them with splines, and ensure they don’t violate curvature rules. But as with any regulation, the devil is in the details—specifically in the loopholes.

The design process begins by placing profiles into this virtual regulation box. The new rules allow for a three-element wing, a significant departure from the simpler main plane and flap configurations of the past. This allows for more aggressive airflow manipulation, but it also introduces a minefield of compliance checks.

Section C of the rules, for instance, dictates that you can only have a single section per volume for X and Y cuts, but allows two for Z cuts. This distinction is crucial because it accommodates “cambered” profiles—wings that curve in three dimensions rather than just running straight across. This curvature is essential for maximizing downforce across the entire width of the car, but it makes manufacturing and legality checks a nightmare.

The “Shadowing” Loophole: Hiding Secrets in Plain Sight

Perhaps the most controversial and exciting discovery in the 2026 rules involves Section E, which regulates concave radii. The rule is intended to prevent teams from creating complex, cavernous shapes that could act as air inlets or extreme vortex generators. It states that there shouldn’t be a concave radius of less than 100mm anywhere on the profile.

However, the regulation defines this limitation based on “visibility.” This is the key. The rule implies that if a part of the wing cannot be “seen” from a specific projection—if it is shadowed by another part of the wing—the strict radius rules might not apply to that hidden area.

This opens a fascinating door for “shadowing.” Theoretically, a team could design a wing element that overlaps another in such a way that it hides a tighter, more aggressive geometry from the official view. In the pre-DRS era, similar tricks were used to hide air inlets (F-ducts) inside profiles. While the utility of an air inlet in a rear wing is debatable today, the ability to create “illegal” shapes by hiding them behind “legal” ones allows for aerodynamic separation bubbles and pressure manipulations that shouldn’t be possible. It is a classic case of the map not matching the territory, and you can bet every team on the grid is currently simulating just how much they can hide in the shadows.

Active Aero: The Strategy of Drag Reduction

The 2026 regulations introduce fully active aerodynamics, a step beyond the current DRS (Drag Reduction System). In this new era, the rear wing flap—defined as the profiles excluding the first main element—can change angle while the car is moving. This means the second and third elements are movable surfaces.

This fundamentally changes how a wing is designed. In the past, you designed a wing for the best compromise between cornering downforce and straight-line drag. In 2026, you design for two distinct states: “High Downforce” and “Low Drag.”

The strategy emerging is simple but brilliant: design the wing so that the majority of the downforce (and therefore the drag) is generated by the movable elements (elements 2 and 3). The main plane (element 1) effectively becomes a foundational flow conditioner. When the car hits a straight and the system activates, elements 2 and 3 flatten out. Because they were carrying the bulk of the aerodynamic load, flattening them sheds a massive amount of drag instantly.

This requires a complete rethinking of the wing’s “angle of attack.” Designers are now positioning the elements to be aggressive in their closed state, often utilizing the maximum allowed 10mm Gurney flap to squeeze every ounce of downforce from the air. But they must also ensure that when the wing opens, the airflow reattaches smoothly and the drag penalty evaporates. It is a binary way of racing: maximum grip in corners, maximum slipperiness on straights.

The “Haas Lesson”: Precision is Paramount

With great complexity comes great risk. The video analysis highlights a critical danger zone in Section G, which mandates a slot gap between 8mm and 12mm between the elements. This gap is critical for maintaining airflow attachment over the multi-element wing.

The FIA polices this with a simple “go/no-go” tool—a stick with a sphere at the tip. If the sphere passes through where it shouldn’t, or doesn’t fit where it should, the car is illegal. This brings to mind the Haas team’s disqualification in Monaco 2024, where a tiny manufacturing or setup error on the extremities of their wing led to a breach of the gap rules.

In 2026, with three elements and complex, cambered 3D surfaces, checking this gap becomes exponentially harder. A gap that is legal in the center of the wing might pinch to 7.9mm on the curved edge due to a slight misalignment or manufacturing tolerance. Teams will need to design with extreme precision, ensuring that their “perfect” aerodynamic surfaces can actually be built and maintained within the chaotic environment of a race weekend. A millimeter of error is the difference between a podium and a disqualification.

Conclusion: A New Era of Engineering

The 2026 F1 car will not just be a new chassis with a new engine; it will be a dynamic, shifting, active machine that exploits every grey area of the rulebook. The “B Sport” design analysis proves that despite the FIA’s best efforts to simplify the sport, engineers will always find a way to complicate it in the pursuit of speed.

From floorboards that recreate the effect of banned components to rear wings that hide their secrets in the shadows of their own geometry, the next generation of Formula 1 is shaping up to be a battle of ingenuity. As we move closer to the launch of these cars, the question isn’t just who has the best engine, but who has read the rulebook closely enough to find the speed hidden between the lines. The race for 2026 has already begun, and it is happening on CAD screens and in wind tunnels long before a wheel turns on the track.