The Ground Effect Experiment: A Rough Ride Ends with a Shocking Admission

As the dust settles on the 2025 Formula 1 season and the sport braces for the dawn of the 2026 regulations, the FIA has done something truly extraordinary: they have admitted they got it wrong.

For four years, teams, drivers, and fans have endured the “Ground Effect” era—a period defined as much by the chaotic, spark-throwing spectacle of “porpoising” as it was by the racing itself. Introduced in 2022 with the noble aim of reducing dirty air and fostering closer wheel-to-wheel combat, the regulations were heralded as a new golden age. Instead, they often delivered physical agony for drivers, confusing disqualifications for teams, and a product that, while occasionally thrilling, fell significantly short of its promises.

Now, as we stand on the precipice of a new era, the governing body has offered a rare mea culpa. But with the controversial re-election of President Mohammed Ben Sulayem looming large over the sport, the question remains: has the FIA truly learned its lesson, or are we destined for another cycle of turbulence?

The Broken Promise of 2022

Cast your mind back to the pre-season excitement of 2022. The sport was saying goodbye to the complex barge boards and over-body aerodynamics of the previous generation, replacing them with venturi tunnels and under-floor downforce. The theory was sound: generate grip from the ground, throw the “dirty” turbulent air upwards, and allow cars to follow one another closely without sliding around helplessly.

“It was meant to be a new dawn,” recalls one paddock insider. “But physics had other plans.”

While the racing did improve in pockets, the overarching goal of eliminating the “dirty air” problem was, by the FIA’s own admission, a failure. The front wings of the new generation still produced significant “outwash,” disrupting the air for the car behind and negating the benefits of the ground effect tunnels. Overtaking remained heavily reliant on the Drag Reduction System (DRS), and the “close following” we were promised often evaporated after a few laps of tire-shredding turbulence.

The “Low Rider” Nightmare and Physical Toll

However, the defining image of this era wasn’t close racing; it was bouncing. “Porpoising”—a term that became part of the vernacular overnight—turned high-tech precision machines into uncontrollable jackhammers.

The cars needed to be run as low to the ground as possible to seal the floor and generate downforce. The result was a violent aerodynamic oscillation that saw drivers’ heads bobbing furiously on straights. It looked almost comical from the outside—like F1 had done a crossover with low-rider culture—but inside the cockpit, it was torture.

Max Verstappen, the dominant force of the era, didn’t mince words. During the Las Vegas Grand Prix, he was heard remarking over the radio, “At times, my whole back is falling apart.” He wasn’t alone. Lewis Hamilton was seen struggling to exit his Mercedes in Baku in 2022, clutching his spine in visible agony.

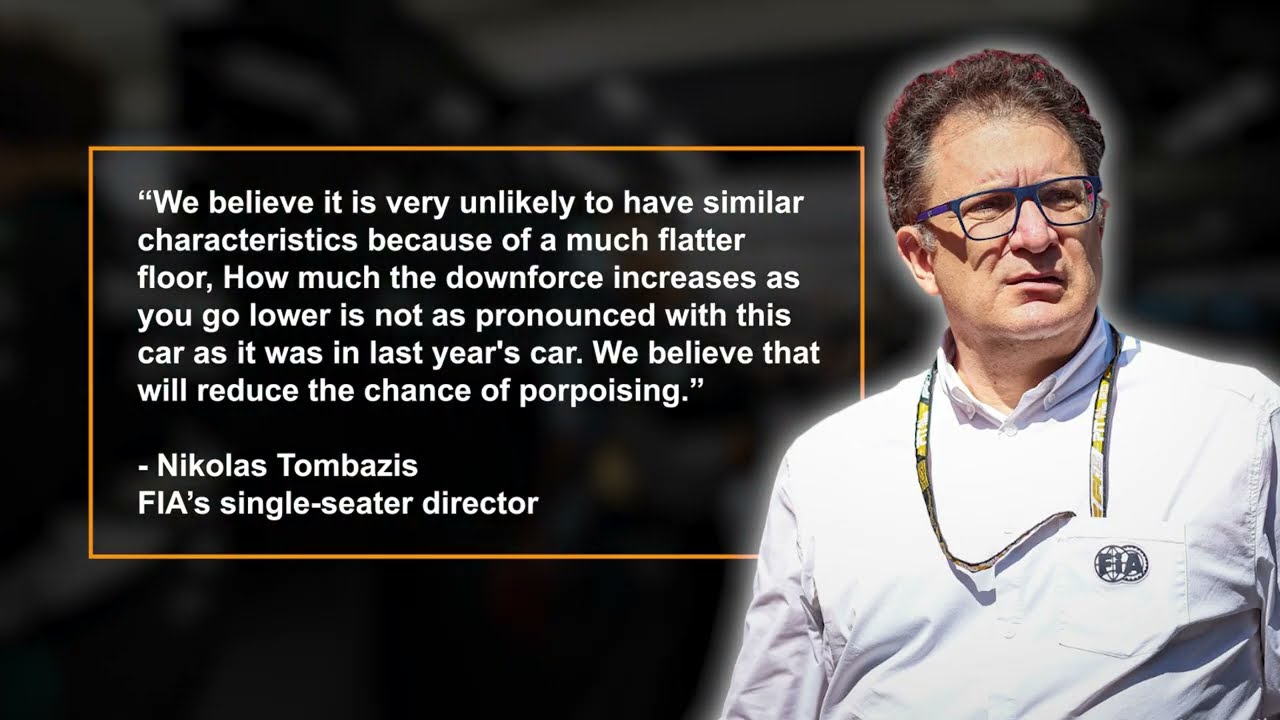

Nicholas Tombazis, the FIA’s Single Seater Director, has now publicly acknowledged that the governing body completely underestimated this phenomenon. “The fact that the optimum ride height of the cars moved so much lower was a miss in the 2022 regulations,” Tombazis admitted recently. “It’s something that we missed, and not only us but also the teams. In all discussions, nobody raised that issue.”

It is a staggering admission of collective blindness. The brightest minds in motorsport failed to predict that sealing a car to the tarmac at 200 mph might cause it to bounce.

The Era of Disqualification

The FIA’s reaction to the porpoising crisis was to police ride heights and plank wear with draconian strictness. If they couldn’t stop the teams from running the cars low, they would punish them for grinding the floor away.

This approach led to some of the most embarrassing moments in recent F1 history. The “Skid Block” became the most talked-about component on the car. Who could forget the 2023 United States Grand Prix, where both Lewis Hamilton and Charles Leclerc were stripped of their hard-earned results hours after the champagne had dried?

But the nadir of this policing strategy surely came at the 2025 Chinese Grand Prix. In a shocking twist that stunned the paddock, both Ferraris were disqualified post-race. Charles Leclerc, who had fought valiantly on a one-stop strategy, was found to be underweight—the result of excessive tire and plank wear grinding the car down. Lewis Hamilton, in his first season with the Scuderia, fell foul of the skid block measurements.

It was a humiliation for the Prancing Horse, but it was also a symptom of a regulatory framework that forced teams to dance on the edge of a razor blade. Even as recently as the Las Vegas Grand Prix, McLaren faced similar scrutiny, proving that four years into the regulations, the fundamental flaw had not been solved.

Tombazis argues that simplifying the suspension rules wouldn’t have had a “first-order effect” on fixing this, a claim many technical directors privately dispute. The result was a sport where fans often had to wait hours after the checkered flag to know who actually won.

Hope for 2026?

So, what changes next? The 2026 regulations promise a departure from the extreme ground effect philosophy. The new cars will feature flatter floors, reducing the suction effect that demands ultra-low ride heights.

“We believe it is very unlikely to have similar characteristics because of a much flatter floor,” Tombazis stated, offering a glimmer of hope. “The chance of porpoising should be reduced.”

In theory, this means cars can run higher, saving drivers’ backs and reducing the risk of post-race disqualifications. But as we learned in 2022, theory and reality in Formula 1 are often miles apart. We won’t truly know until the cars hit the tarmac in Spain for pre-season testing at the end of January.

The Unopposed President

While the technical regulations are shifting, the political landscape remains stubbornly static. Amidst the admissions of regulatory failure, Mohammed Ben Sulayem has been re-elected as FIA President for a second four-year term, ending in 2029.

The election itself has drawn sharp criticism for its lack of democratic vigor. Ben Sulayem ran unopposed—a situation brought about by a quirk in the FIA’s statutes that requires candidates to name a slate of vice-presidents from every global region. With key figures already aligned with the incumbent, potential challengers like American Tim Mayer and Swiss Laura Villas found it mathematically impossible to form a ticket.

Despite running alone, Ben Sulayem secured only 91.51% of the vote. That nearly 9% of eligible clubs chose to abstain rather than endorse the only candidate speaks volumes about the underlying tensions within the federation.

A “FIFA-Style” Governance?

Ben Sulayem’s first term was characterized by what critics call an “interventionist” style. From public spats with drivers over jewelry and underwear to accused interference in race results, his tenure has rarely been quiet. His administration has seen a purging of internal opponents and a restructuring of power that some observers have darkly compared to the FIFA corruption scandals of 2015—consolidation of power under the guise of “reform.”

The FIA’s official statement following his re-election praised his “wide-ranging transformation” and “improved transparency.” Yet, for many in the paddock, these claims ring hollow against a backdrop of constant friction between the governing body and the commercial rights holders (FOM), as well as the teams themselves.

The Road Ahead

As we look toward 2026, Formula 1 finds itself at a crossroads. On the track, we have a new set of rules designed to fix the “big mistakes” of the past four years. We have the promise of cars that don’t destroy drivers’ spines and a regulatory environment that hopefully relies less on the measuring tape and more on the stopwatch.

But off the track, the re-election of a polarizing figure suggests that the drama is far from over. The FIA has admitted its technical faults, but whether it can address its governance issues remains to be seen.

For the fans, the hope is simple: let the 2026 headlines be about the racing, not the rulebook. After four years of “dodgy” regulations and political infighting, the sport deserves a clean slate. Whether the FIA can deliver one, however, is the biggest question of all.