The world of Formula 1 is perpetually in motion, not just on the track, but in the sterile, silent wind tunnels and digital landscapes where the future of the sport is forged. With the 2026 regulations looming on the horizon, promising a new dawn of sustainability and spectacle, fans and teams alike are scrambling to understand what these machines will actually look like—and more importantly, how they will race.

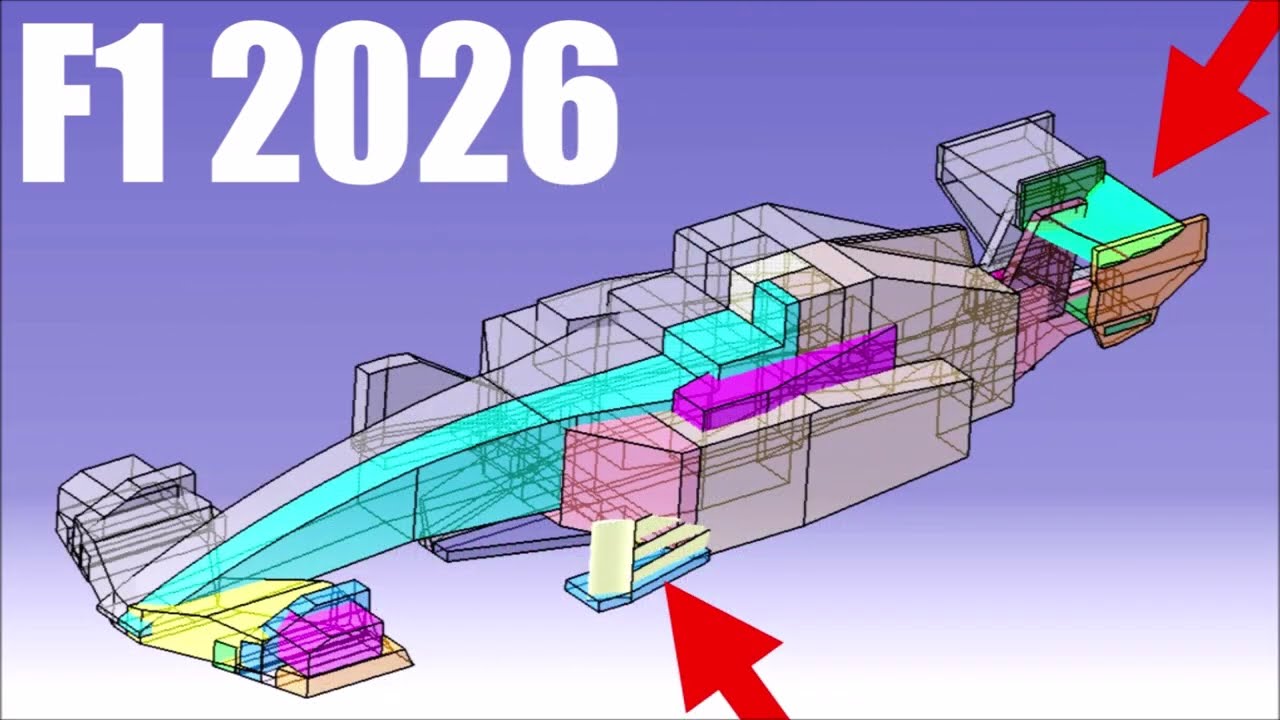

Until now, much of the conversation has been theoretical. We’ve seen regulation boxes, read dense technical documents, and speculated on the impact of active aerodynamics. But thanks to a groundbreaking collaboration between talented car designer Emir and the simulation experts at Airshaper, we now have something far more tangible: a fully designed, three-dimensional representation of a 2026 Formula 1 car, subjected to a rigorous Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) analysis.

The results? They are as fascinating as they are worrying. While the car is a visual stunner, blending futuristic aggression with retro cues, the aerodynamic data suggests that Formula 1 might be sleepwalking back into a problem it spent years trying to solve: the dreaded “dirty air.”

The Experiment: 100 Million Cells of Truth

Before diving into the alarming conclusions, it is vital to appreciate the scale of this analysis. This wasn’t a quick sketch thrown into a basic wind tunnel app. Emir, a designer who has poured over a year into interpreting the 2026 rulebook, created a model that is arguably the most accurate public representation of the next generation of F1 machinery.

To validate this design, the model was processed by Airshaper, a cloud-based CFD platform. They didn’t cut corners. They utilized an “adaptive mesh refinement” technique—the same high-level simulation settings used by engineers like Lucas di Grassi for the Generation 5 Formula E cars. The simulation crunched data across 100 million individual cells. In layman’s terms, this is a heavy-duty, industrial-grade virtual wind tunnel test. It allows us to see the invisible: the pressure zones, the chaotic vortices, and the energy streams that will define the 2026 World Championship.

A Blast from the Past: The Visual Identity

At first glance, the 2026 car feels eerily familiar. If you’ve been following the sport for a decade, you might feel a pang of nostalgia. The design language seems to echo the pre-2019 era of Formula 1.

The front wing is a prime example. It returns to a three-element design, where the top two elements are adjustable, allowing them to change angle on the straights—a key part of the new active aero ethos. The complex “upper deflectors” over the wheels, which define the current grid, are gone. In their place, we see the return of “strakes” on the front wing and specific elements on the endplates designed to desperately guide air around the massive obstruction of the front tires.

The suspension layout on this concept utilizes a push-rod configuration at both the front and the rear. Moving further back, the floor concept has shifted again. We are looking at a flat floor equipped with multiple vanes and a “floorboard” featuring intricate vertical and horizontal elements. It’s a departure from the pure ground-effect tunnels of today, blending old philosophies with new restrictions.

The sidepods are wide, featuring a massive undercut—a sculptured area beneath the air intake intended to channel clean air to the rear of the car. The rear wing sports traditional endplates again, and the cooling exits are wrapped tightly around the exhaust pipe. It looks fast, it looks aggressive, and it looks like a Formula 1 car. But as any aerodynamicist will tell you, looking fast and racing well are two very different things.

The Front Wheel Problem

The simulation begins at the front, where the air is “red”—meaning it is full of high energy, undisturbed and ready to be used to generate downforce. But as soon as the car punches a hole in this air, the chaos begins.

The biggest enemy of aerodynamic efficiency in open-wheel racing is the front tire. It is essentially a spinning wall of turbulence. The simulation clearly shows how the wake—the disturbed air—from the front wheels is a massive headache. If this “dirty” low-energy air hits the floor or the rear wing, the car loses grip instantly.

In the current ground-effect era, teams use powerful “out-washing” aerodynamic devices (like the now-banned bargeboards) to punch this tire wake far away from the car body. The 2026 rules, however, have removed many of these tools. There is no bargeboard area. Instead, the car features an “in-washing” floorboard.

The CFD analysis highlights a struggle here. The vane behind the front wheel attempts to push the middle section of the tire wake outward. The floorboard tries to pressurize the air to help this process. In the simulation, it works reasonably well for the middle part of the wake, but the upper and lower sections are problematic. The lower wake crashes into the outboard part of the floor, and the upper wake stays stubbornly close to the bodywork. Teams will have to work overtime to fix this, because if that wake isn’t managed, the car becomes unpredictable.

The “Bleeding” Car: Energy Losses and Separations

Designers use “X-cuts”—cross-sectional slices of the air pressure around the car—to diagnose health. In an ideal world, you want to maintain high energy (red colors) as far back as possible. This 2026 simulation, however, shows a car that is “bleeding” energy in worrying places.

We see flow separation (where the air stops sticking to the car and becomes turbulent) occurring at several key points:

The Front Wing Mountings: Creating immediate losses that flow downstream.

The DRS Actuator: A necessary evil that disrupts the airflow in the center.

The Sidepod Inlets: The simulation picked up a separation from the outboard side of the inlet, suggesting that teams will need to refine the radius and shape of these openings to keep the air attached.

The Floorboard: The lower horizontal element creates a “big separation,” essentially a pocket of dead air that causes trouble further down the car.

These might sound like minor technical quibbles, but in F1, they are the difference between pole position and P10. The bodywork drags these losses down into the diffuser area—exactly where you don’t want them. The goal is to create a clear path for “bad” air to exit between the beam wing and the rear wing, but the simulation shows it’s a messy process.

The Return of the “Dirty Air” Nightmare?

This is the bombshell of the analysis. The most critical takeaway from this 100-million-cell simulation is the quality of the wake left behind the car.

Since 2022, Formula 1 has been on a crusade to clean up the wake. The goal was to throw the turbulent air upwards (the “mushroom” effect) so the car behind drives through clean air. This simulation suggests 2026 might undo that hard work.

The analysis reveals that the car generates a “huge and dirty wake.” The tip vortices from the rear wing do support some upwash, but the center of the wake is dominated by two large separation bubbles caused by the rear wing mountings.

The narrator delivers a sobering verdict: “It seems like F1 will introduce old problems again.”

Ideally, the air behind the car should be red (high energy). But the simulation shows a massive blue zone (low energy/turbulence). For a trailing car, this is a disaster. The 2026 cars are set to rely more on downforce generated by the wings (rather than just the floor). Wings are notoriously sensitive to dirty air. If you put a wing-dependent car into a dirty wake, it loses a huge percentage of its grip.

This creates a vicious cycle:

The lead car creates a dirtier wake than current cars.

The following car relies more on wings for grip.

The following car loses more grip when it enters the wake.

Following becomes harder, and overtaking becomes a struggle.

It paints a picture of a formula that might be physically faster on the straights due to active aero, but potentially much worse for wheel-to-wheel combat in the corners.

The Cornering Crisis

The simulation was conducted in a straight line, which is the “best case scenario” for aerodynamics. The analysis points out a terrifying prospect for cornering.

The upper wake from the front wheels sits dangerously close to the rear wing. In a straight line, it just misses it. But as soon as the driver turns the steering wheel entering a corner, that wake could swing sideways and smash directly into the rear wing.

Imagine driving a car at 180 mph. You turn in, relying on your rear wing to stick the back of the car to the road. Suddenly, a burst of turbulent air from your own front tires hits the wing, and you lose 20% of your downforce in a split second. The rear snaps, the driver loses confidence, and they have to back off. This “instability” could make the 2026 cars incredibly tricky to drive on the limit, forcing teams to play it safe with setup and driving styles.

The Engineering Battleground

Of course, this is a “generic” design based on the rules. It represents the starting point. The genius of engineers like Adrian Newey or James Allison lies in solving these exact problems.

The video identifies the key battlegrounds for the teams:

Pushing the Wake Outboard: Teams will use every millimeter of the mirrors, mirror stalks, and suspension arms to shove that dirty front-tire wake away from the car.

Sidepod Shaping: Expect to see wider sidepods used as shields, keeping the floor clean by pushing losses outboard for longer.

The “Clean Ditch”: There is a promising channel of clean air going down to the top of the diffuser. Protecting this channel will be the number one priority for aerodynamicists.

Conclusion: A Warning Sign?

This complex CFD simulation serves as a fascinating, if slightly alarming, window into the future. Thanks to Emir’s meticulous design and Airshaper’s computing power, we can see that the 2026 regulations are not a magic bullet. They present a car that looks more traditional but brings with it the aerodynamic baggage of the past.

If the simulation holds true, the sport faces a paradox: advanced active aerodynamics and sustainable engines packaged in a chassis that might struggle to race closely. The “dirty wake” is back, and it looks bigger and badder than before.

As we inch closer to 2026, the question remains: Can the teams engineer their way out of these regulations, or are we destined for a return to the “processional” races of the past? Only time—and perhaps a few more hundred million CFD cells—will tell. But for now, the warning lights are flashing red in the virtual wind tunnel.