On August 23, 1987, the calm waters off the Isle of Wight were shattered by the roar of high-performance engines. The Colibri, a powerboat piloting at nearly 170 km/h, hit the wake of the oil tanker Esso Avon and launched into the air. When it crashed back down, there was only silence—the kind of final, suffocating silence that signals the end of a story .

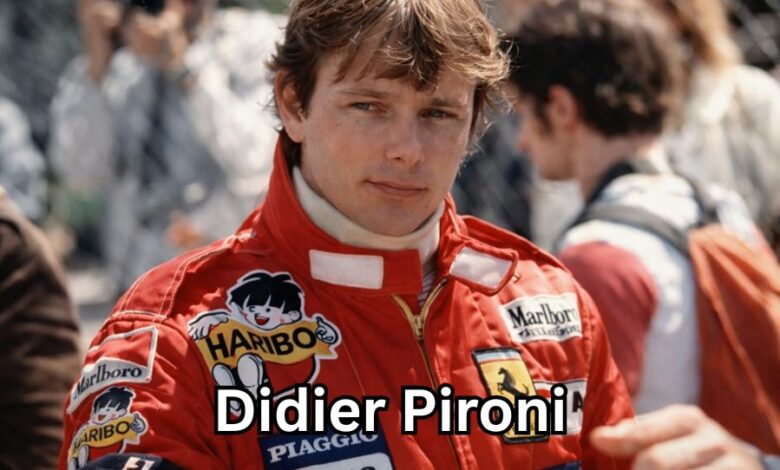

Didier Pironi was just 35 years old. To the world, he died as a complicated, often vilified figure. He was the man who “stole” victory from the beloved Gilles Villeneuve at Imola in 1982, sparking a feud that many believe led to Villeneuve’s death just 13 days later. He was the “nearly man,” the championship leader whose F1 career was cut short by a horrific crash that shattered his legs. He was seen as a cold, calculating engineer in a sport of romantic daredevils.

But the public narrative missed the heart of the man. Pironi never wrote a memoir. He never sat for a tell-all interview to list the drivers he respected. Instead, he wrote his list in the choices he made, the mentors he grieved, and the courage he borrowed when his own reserves ran dry. His life was shaped by five specific drivers—five men who taught him how to live, how to race, and ultimately, how to die .

1. Gilles Villeneuve: The Brother He “Betrayed”

The most defining relationship of Pironi’s life was undoubtedly with Gilles Villeneuve. When Pironi arrived at Ferrari in 1981, he wasn’t met with hostility; he was met with brotherhood. Villeneuve, the flamboyant French-Canadian who drove “the way other people dream,” welcomed Pironi into his life. They shared meals, traveled together, and raced rental cars on Italian motorways with a joy that transcended competition .

Pironi, the logical engineer who processed the world through calculation, was mesmerized by Villeneuve’s “luminous” freedom. He admired the very thing he could never be: a driver who felt first and thought later. Villeneuve was instinct; Pironi was intellect. It was a perfect pairing—until Imola 1982.

That day, a “Slow” sign from the Ferrari pit wall tore them apart. Villeneuve interpreted it as “hold position”; Pironi saw it as “be careful but race.” Pironi passed Villeneuve on the final lap to take the win. Villeneuve, feeling stabbed in the back by the man he treated like family, declared “absolute war” . Less than two weeks later, while pushing desperately to beat Pironi’s qualifying time at Zolder, Villeneuve was killed.

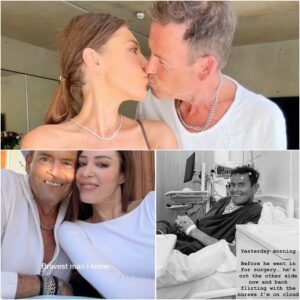

The paddock turned on Pironi. He was cast as the villain in a Shakespearean tragedy. Yet, Pironi never defended himself. He never spoke a bad word about Gilles. Instead, he carried the grief in silence. Years later, when his girlfriend Catherine Goux gave birth to twins after Pironi’s own death, she named them Didier and Gilles—a permanent, heartbreaking confession of the bond that even death and “betrayal” could not sever .

2. Patrick Depailler: The Mentor Who Taught Survival

Before the drama of Ferrari, there was the education at Tyrrell. In 1978, a young and unfinished Pironi was paired with Patrick Depailler. Depailler was older, battle-hardened, and wise to the dark arts of Formula 1. He taught Pironi what couldn’t be found in data sheets: how to read a circuit’s evolving grip, how to manage the fragile ego of an engineer, and how to carry the crushing weight of pressure without cracking .

But it was Depailler’s resilience off the track that truly shaped Pironi. After shattering his legs in a hang-gliding accident in 1979, Depailler returned to the cockpit before he could even walk properly, simply because “sitting still was not something he knew how to do” . When Depailler was killed in a testing crash at Hockenheim in 1980, Pironi was devastated. He stayed close to Depailler’s family, absorbing the cruel reality of the sport. Two years later, at the very same circuit, Pironi would face his own life-altering crash, drawing on the memory of his mentor’s refusal to quit.

3. Tazio Nuvolari: The Legend of “Will Over Physics”

Not all heroes are contemporaries. Some are ghosts. At Maranello, Enzo Ferrari—the “Commendatore”—often spoke of Tazio Nuvolari with a reverence reserved for saints. Nuvolari raced in an era of leather helmets and zero safety, winning not because he had the best car, but because he refused to accept defeat as a possibility .

Nuvolari was known for pushing broken cars across finish lines and racing through illness and pain. For Pironi, a man of science and “marginal gains,” Nuvolari represented the irrational, magical element of racing: the idea that sheer human will could override the laws of physics. Pironi listened to Enzo’s stories like “a young architect studies a cathedral,” trying to understand the source of that impossible strength . It was a lesson he would need when he found himself lying in a hospital bed, told he would never walk, let alone race, again.

4. Alain Prost: The Mirror Image

If Villeneuve was the opposite of Pironi, Alain Prost was his reflection. Both men were products of the famous Elf Winfield Racing School; both approached racing as a “problem to be solved” rather than a sensation to be chased. Pironi admired Prost’s “chess player” mind—the ability to drive slower to finish faster, to conserve tires when others were burning them up .

Their connection, however, was sealed in violence. On that fateful wet morning at Hockenheim in 1982, Pironi, blinded by spray, launched off the back of Prost’s Renault. The crash ended Pironi’s career instantly. Prost later admitted that seeing Pironi’s Ferrari fly over him changed his psychology forever, instilling a permanent caution in wet conditions . Yet, the accident didn’t breed resentment. Instead, it created a silent, tragic bond between the two Frenchmen—one who went on to become a four-time champion, and one who was forced to watch from the sidelines, wondering “what if.”

5. Niki Lauda: The Blueprint for Resurrection

When Pironi lay in the hospital, his legs shattered and his career in ruins, he didn’t look to comforting words. He looked to facts. And the ultimate fact was Niki Lauda. Pironi knew the story of Lauda’s 1976 Nurburgring fire—the near-death experience, the last rites, and the impossible return to Monza just 42 days later with his wounds still bleeding .

To Pironi, Lauda wasn’t just an inspiration; he was “clinical, documented proof” that a broken body could return to the grid. Lauda’s comeback became the “fixed point” Pironi navigated by during years of agonizing rehabilitation. He endured over 30 surgeries, measuring progress in millimeters, driven by the belief that if Lauda could do it, so could he .

And he almost did. By 1986, Pironi was testing F1 cars again, lapping within a second of the regulars. He was physically ready. But the sport had moved on. Insurance complications and a changing political landscape closed the door, forcing him to find a new outlet for his adrenaline: powerboat racing.

The Circle Closes

Didier Pironi’s life was a tragedy of timing. He learned from the best, fought the hardest, and lost it all just as he was on the brink of glory. But the story didn’t end in the water off the Isle of Wight.

Decades later, in 2020, a Mercedes engineer stood on the podium at Silverstone to accept the Constructors’ Trophy. His name was Gilles Pironi. The son Didier never met, named after the friend he never stopped loving, had returned to the pinnacle of motorsport, methodical and successful, just like his father.

Pironi’s “list” was never written down, but it was etched into his soul. From Villeneuve’s spirit to Depailler’s grit, Nuvolari’s will, Prost’s mind, and Lauda’s resilience—he carried them all with him into the cockpit of the Colibri. And in the end, as the inscription on his grave reads, he remains forever “Entre Ciel et Mer”—between sky and sea, exactly where he always belonged.