A dog trains to recover a “wounded” soldier in 1917. (Imperial War Museums)

In the agony of trench warfare and no man’s land, the sound of a skitter and a wet nose — typically a rat, doubled in size after gorging on the flesh of man — usually spelled trouble.

But occasionally, the wet nose brushing across both Allied and Central Power soldier’s faces meant that help, or at the very least comfort, was on its way.

Over 16 million total animals were in service during the Great War, with dogs hauling machine guns and supply carts, serving as messengers and delivering the all-important cigarette cartons to the troops.

However, Mercy Dogs, also referred to as casualty dogs, were specifically trained to aid the wounded and dying on the battlefield. First trained by the Germanic armies in the 19th century, these sanitätshunde, or medical dogs, began to see widespread use as World War I swept across Europe.

Trained to find and distinguish between the dead, wounded and dying, Mercy Dogs were set loose on the battlefield to bring medical supplies to the wounded, “getting as close as possible so the soldier could access the dogs’ saddle bags, which contained first aid supplies and rations. Instead of barking and alerting the enemy, the dogs were trained to bring back something belonging to the soldier,” according to the Red Cross.

The dogs were trained in triage, able to indicate who needed aid the most and who was too far gone to establish any medical care. In the case of the latter, the dog would often stay with the mortally wounded soldier to ensure that, in his final moments, he wasn’t alone.

The idea of Mercy Dogs was first introduced in 1890 by German painter, Jean Bungartz, who founded the Deutschen Verein für Santiätshunde or German Association for Medical Dogs.

Five years later, Britain took notice after Maj. Edwin Richardson observed that English-bred dogs were being shipped to Germany in bulk.

“I took notice of a ‘foreigner’ buying a sheepdog from a shepherd and learned that the man was a German, sent over by his government to purchase large quantities of collie dogs for the German Army,” Richardson recounted.

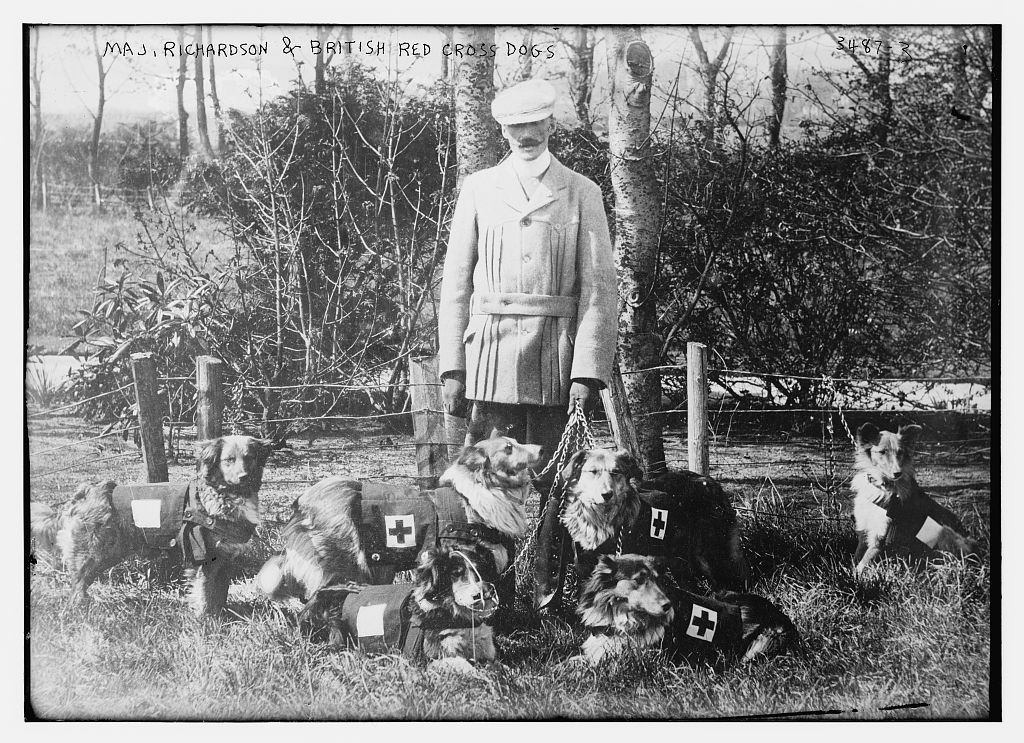

Maj. Edwin H. Richardson with Red Cross war dogs during World War I. (Library of Congress)

Maj. Edwin H. Richardson with Red Cross war dogs during World War I. (Library of Congress)

Seeing a similar need, Richardson and his wife opened the British War Dog School, just prior to the outbreak of war in 1914 — the first of its kind in the nation. While Richardson trained several different breeds, his favorite was Airedales for their intelligence, devotion and coolness under fire.

Trained under realistic battle conditions, one visiting journalist recounted that “Shells from batteries at practice were screaming overhead, and army motor lorries passed to and fro. The dogs are trained to the constant sound of the guns and very soon learn to take no heed of them.”

Once on the Western Front, these dogs “not only had to survive but to perform critical duties in ghastly conditions which saw the natural world obliterated daily — grass was virtually nonexistent, trees were blown to pieces or harvested into oblivion for wood, the air was rife with poisonous gases in addition to the sounds and shell fragments of explosions, water was contaminated with heavy metals, decomposing bodies were omnipresent and the earth’s surface tended to be wildernesses of bomb craters or oceans of mud,” writes MHQ editor, Zita Ballinger Fletcher.

Under these conditions, the animals silently toiled, utilizing their noses and devotion to ultimately save roughly thousands of lives, according to the Red Cross.

One British surgeon noted, “They sometimes lead us to bodies we think have no life in them, but when we bring them back to the doctors…always find a spark. It is purely a matter of their instinct, [which is] far more effective than man’s reasoning powers.”

In 1915, British soldier Oliver Hyde published a long-forgotten work entitled “The Work of the Red Cross Dog on the Battlefield.”

In it, he captures the small but mighty group of heroes:

“To the forlorn and despairing wounded soldier, the coming of the Red Cross dog is that of a messenger of hope.

“Here at last is help, here is first aid. [The soldier] knows that medical assistance cannot be far away, and will be summoned by every means in the dog’s power.

“As part of the great Red Cross army of mercy, he is beyond price.”

Tragically, albeit unsurprisingly, a large number of Mercy Dogs died during the war. By the time the Armistice was signed on Nov. 18, 1918, some 7,000 Mercy Dogs had been killed in service to their respective countries.