In the high-octane world of Formula 1, history is often written by the victors, but memory is shaped by the emotional. We worship the daredevils, the poets of speed who dance on the razor’s edge with fire in their eyes and their hearts on their sleeves. We canonize the reckless bravery of a Gilles Villeneuve or the spiritual intensity of an Ayrton Senna. But what happens to the man who refuses to dance? What happens to the champion who treats the sport not as a theater of death, but as a solvable equation?

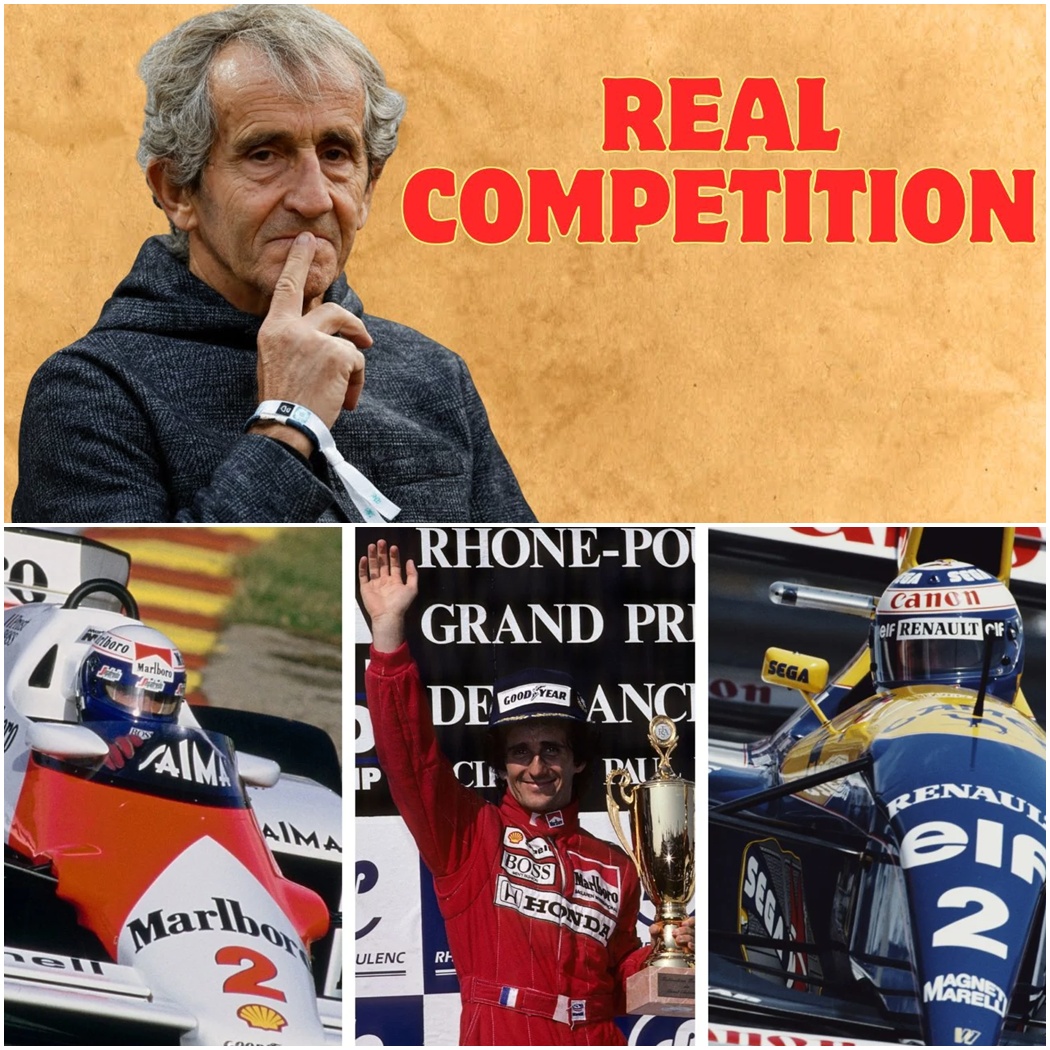

Alain Prost, the four-time World Champion known universally as “The Professor,” has long been the antagonist in the mythology of Formula 1. He was the Salieri to Senna’s Mozart—the calculated, cold, and political counterweight to raw, unadulterated talent. But this narrative, while convenient, is a hollow simplification. To understand Prost is to understand a man who was not merely racing against other drivers; he was waging a philosophical war against the very nature of the sport.

At 70 years old, looking back on a career decorated with 51 victories and four crowns, Prost’s legacy is not defined by the trophies in his cabinet. It is defined by the scars left by five specific entities—five rivalries that pushed him, broke him, and ultimately revealed the depth of his character. These were not just on-track skirmishes; they were collisions of ideology, ego, and betrayal that paint a portrait of a genius isolated by his own intellect.

The Philosophical War: Ayrton Senna

To discuss Prost without Senna is impossible, like trying to describe a shadow without the light. But their rivalry was never just about who was faster. It was a violent clash of two irreconcilable worldviews.

When Ayrton Senna joined McLaren in 1988, he brought with him a messianic belief that he was destined to win, that God was his co-pilot, and that a gap on the track was an invitation from the divine. Prost, conversely, was a man of logic. He raced with the probability percentages running through his mind. He conserved his tires, saved his fuel, and accepted second place if it meant securing the championship.

To Senna, Prost’s caution was cowardice. To Prost, Senna’s aggression was insanity.

The tragedy of their rivalry wasn’t just the crashes; it was the total disintegration of trust. The breaking point at Suzuka in 1989—the infamous collision at the chicane—was the moment their cold war went nuclear. When they touched, Prost climbed out of his car, his race done. He had calculated the risk and made his move. Senna, fueled by a refusal to accept defeat, rejoined and won, only to be disqualified.

The narrative that followed was devastating for Prost. He won the title, but he lost the people. He was painted as the manipulator who used his connections to steal glory from the “people’s champion.” Then came Suzuka 1990, where Senna deliberately rammed Prost at 160 mph in the first corner—a move of terrifying nihilism. Senna later admitted it was premeditated. For Prost, this wasn’t racing; it was madness. It forced him to confront a sport that was willing to reward endangerment if it came wrapped in charisma. He didn’t just hate Senna for the crash; he hated that the world cheered for it.

The Clash of Egos: Nigel Mansell

If Senna was the enemy of Prost’s mind, Nigel Mansell was the thorn in his side. Their partnership at Ferrari in 1990 was doomed from the start. Mansell, “Il Leone” (The Lion), was pure emotion—a driver who wrestled the car with brute force and wore his heart on his racing suit. The Italian fans, the Tifosi, loved him for it.

Then came Prost: precise, authoritative, and politically astute. Mansell immediately felt his territory being encroached upon. He became convinced that Ferrari—and Prost—were conspiring against him. He saw shadows where there were none, believing Prost was hoarding the best equipment and the team’s attention.

The reality was simpler but far more bruising for Mansell: Prost was just better at managing a team. While Mansell raged at the mechanics and played the victim, Prost was in the debrief room, meticulously analyzing data and directing development. Prost didn’t need to sabotage Mansell; his method was the sabotage. It highlighted every deficiency in Mansell’s chaotic approach.

This rivalry was personal. It was a daily grind of paranoia and passive-aggression. Mansell felt betrayed by a team he loved; Prost felt burdened by a teammate he couldn’t respect professionally. It wasn’t a war of crashes, but a war of atmosphere—a toxic cloud that hung over the garage, proving that in F1, your deadliest enemy is often the man wearing the same shirt.

The Cold War: Nelson Piquet

While Senna and Mansell were loud, visible threats, Nelson Piquet was the sniper in the bushes. Piquet and Prost were contemporaries, rising through the ranks together, both sharing a cerebral approach to driving. But where Prost used his intelligence to build, Piquet used his to destroy.

Piquet was the grid’s provocateur, a man who delighted in psychological torture. He didn’t just want to beat you; he wanted to humiliate you. He famously referred to Mansell as an “educated blockhead” and insulted Enzo Ferrari’s age. But with Prost, the disdain was quieter, more intellectual.

Prost viewed Piquet as a wasted genius—a man of immense talent who treated the sport with a lack of seriousness that bordered on insult. Piquet viewed Prost as uptight and politically protected. Their rivalry was a cold war of sarcastic comments and dismissive glances.

Prost couldn’t stand Piquet’s unpredictability. Prost craved order; Piquet thrived in chaos. To the Professor, Piquet was “noise”—a distraction that didn’t deserve his energy. Yet, the sting was there. Piquet was the mirror Prost didn’t want to look into: a reminder that intelligence could be used for malice just as easily as for victory. It was a rivalry of mutual, silent contempt, proving that sometimes the people we dislike the most are the ones who refuse to play by our rules of engagement.

The Betrayal: Ferrari

Perhaps the most heartbreaking rival in Prost’s career wasn’t a person at all—it was a machine, and the institution behind it.

Prost joined Ferrari in 1990 as a savior. He was the man to bring the title back to Maranello. And he almost did, dragging a good car to the brink of glory against the superior McLaren of Senna. But by 1991, the dream had rotted.

Ferrari has always been a team driven by passion, national pride, and politics. Prost, the man of cold logic, was an imperfect fit for a team that ran on hot blood. As the 1991 car, the Ferrari 643, proved to be uncompetitive, the relationship crumbled. Prost, ever the honest technician, gave feedback that the team didn’t want to hear.

The climax came when he famously described the car’s handling as being like a “truck.” It was a colloquialism, a moment of frustration from a driver wrestling a heavy steering wheel. But in Italy, it was blasphemy. Ferrari didn’t just reprimand him; they fired him before the season even ended.

Think about that: a three-time world champion (at the time), fired for telling the truth. It was the ultimate betrayal. Prost had given them everything—his expertise, his driving, his leadership—and they sacrificed him to save face. It reinforced Prost’s cynical view of the world: that politics and ego would always trample competence. He didn’t lose to a better driver; he lost to a dysfunction he couldn’t fix.

The Puppeteer: Jean-Marie Balestre

Finally, there is the specter of Jean-Marie Balestre, the authoritarian President of the FIA. History has often lumped them together, viewing Prost as Balestre’s “pet” countryman, the beneficiary of French favoritism. The disqualification of Senna at Suzuka ’89 is the smoking gun for conspiracy theorists everywhere.

But the truth is far more nuanced and painful for Prost. Being perceived as the “teacher’s pet” destroyed his reputation. Prost wanted to win because he was the best, not because the referee was on his side. He despised the chaotic, autocratic way Balestre ran the sport just as much as Senna did.

Prost needed rules. He needed a framework where intelligence could triumph. Balestre represented the arbitrary application of power. When the FIA interfered, it delegitimized Prost’s achievements. He won the 1989 title, but Balestre’s heavy-handed involvement meant he never truly got to celebrate it. The trophy was his, but the honor was tainted by the perception of politics.

Balestre wasn’t a rival on the track, but he was a rival to Prost’s legacy. He represented the “structure” that Prost could never defeat. No matter how fast he drove, he couldn’t outrun the accusations of favoritism. It was a burden he carried unfairly, a stain on his record that he had no hand in creating.

The Legacy of the Professor

So, who is Alain Prost?

He is not the villain the movies make him out to be. He is a tragic figure of immense brilliance. He was a man who brought a slide rule to a knife fight. He believed that Formula 1 should be a meritocracy of man and machine, a test of discipline and intellect. Instead, he found himself trapped in a soap opera of egos, politics, and fanaticism.

His rivalries with Senna, Mansell, Piquet, Ferrari, and the FIA reveal a man who was constantly fighting to impose order on a chaotic world. He was the adult in the room, and as any child knows, the adult is rarely the fun one.

Today, we can look back and see the truth. We can appreciate the smoothness of his driving, the economy of his movement, and the sharpness of his mind. We can see that his caution was actually wisdom, and his “politics” were often just a desperate attempt to survive in a piranha tank.

Alain Prost was the greatest driver of his generation who never needed to show off. And perhaps that was his only sin. In a sport that demands heroes and villains, he refused to play a character. He just wanted to be the Professor. And in the end, the lesson he taught us was the hardest one of all: that sometimes, being right is the loneliest place to be.